Flutes of the Middle Ages

Any attempt to chart the lineage of medieval flutes means juggling a mixed bag of evidence: archaeological bits, manuscript images, the odd literary references sneezing themselves into history. And as if these waters were not confused enough, there comes the sudden squall of a Renaissance treatise crashing in from the future with opinions nobody asked for.

What you end up with, in the end , is not a neat, linear history, but a cautious, tip-toeing map of maybes . There's the occasional transverse flute, drifting through pastoral scenes and brushing up against the iconography of Krishna; the more user-friendly duct flute, obligingly sounding without the acrobatics of embouchure; and vessel flutes such as the faintly mysterious gemshorn. Taken together, they point to a medieval Europe supporting a rambunctious family of wind instruments, each with its own regional accent, differing in material, construction, and social function.

The Symbolic Bit

Flutes have always been up to something symbolic, and the Middle Ages were hardly immune to their mischief. They cling closely to the human voice, hovering in that suggestive space between speech, song, and breath, and in doing so position themselves as a kind of go-between, linking humans to the wider, ungovernable world outside the walls.

See A User's Guide to Medieval ShapeshiftinG

The flute has been scheming with symbolism for ages. The Greeks were already at it, wiring the instrument into the myth of Syrinx and Pan, where breath, desire, and vegetal transformation blur into one another. In the Baroque period, the recorder in particular was linked to themes such as the pastoral, sexuality, water, lamentation, and the supernatural. Throughout history, the flute has been seen as a symbol of rural life and nature.

Beyond its Western habit of loitering in fields , the flute holds deep symbolic meaning in Eastern traditions. The transverse flute, believed to have originated in India, is closely linked with Krishna. Here, the instrument is not just a symbol of pastoral life, but a representation of the human heart. Rumi got poetic about it: human suffering = the holes in the flute. God = the player. The reed shaped by suffering = your feelings, probably.

The Problem With the Evidence

If we want to know anything more, we're forced to start rummaging: iconography, literature, and whatever battered instruments happened to survive. And of course, none of it wants to play nice. Later images are already contaminated by Renaissance developments, happily projecting newer, shinier instruments backwards in time. Yes, this tells us something about how things evolved , but it does precious little to pin down what medieval instruments actually looked or sounded like. The Renaissance period witnessed significant advancements in musical instrument design, which complicates our efforts to learn about their earlier medieval counterparts.

A case in point is the frestel , the medieval panpipe. What little we think we know (culled from iconography and the odd surviving specimen) suggests an instrument carved from a single block, punctured with five to seven holes, monolithic rather than modular. Then you wander into the Renaissance archives, and the trail collapses like a drunken lute player in a gutter. The panpipes pictured in the Sforza Hours, for instance, are less evolutionary cousins than anatomical strangers: ducted contraptions conspicuously absent from the medieval record. Leap forward again to Praetorius's Syntagma Musicum , and the resemblance becomes purely nominal: panpipes in name, perhaps, but in form and function something else entirely. Add to this the elegantly curved panpipes later cultivated in the Ottoman world, and the confusion only deepens. These instruments illuminate many things, but the medieval frestel is not one of them. Rather than clarifying the past, they underline it: a reminder that musical history is not a continuous line but a series of false leads, discontinuities, and alluring but ultimately irrelevant evidence.

The tabor pipe , when viewed through the Renaissance lens, appears reassuringly legible: a family of instruments in graded sizes, obligingly standardised, their three finger-holes corralled at the distal end as if by regulatory fiat. Treatises such as Orchésographie, along with the printed dance collections churned out by Pierre Attaingnant, Tielman Susato, and Pierre Phalèse, present the pipe-and-tabor as a kinetic engine of social movement: portable, efficient, and perfectly adapted to the rhythmic imperatives of dance. One could be forgiven for assuming this configuration had always been thus.

But medieval images tell a less cooperative story. Here the pipe is frequently played one-handed, yes, but not gripped at its lower extremity in the manner later taken for granted. The hand wanders; the posture shifts. The implication is awkward but unavoidable: the familiar Renaissance layout of finger-holes may be an historical imposition rather than a continuity.

In other words, we may be projecting backward a technique that simply didn’t exist yet.

Compounding the problem is the relative silence of medieval texts on the pipe's relationship to dance. Unlike its Renaissance afterlife, where it becomes almost synonymous with choreographed motion, the medieval pipe seems to occupy a more ambiguous sonic niche, its function under-described and its social role oddly opaque. What emerges is not a primitive version of a later certainty, but a different instrument altogether, retrospectively tidied up by historians unwilling to tolerate discontinuity.

This issue of assuming continuity between the medieval and Renaissance instruments is not isolated to the pipe and tabor. Similar considerations apply to instruments found in both periods. It is important to resist the notion that instruments necessarily evolved in a linear progression from simple to more complex forms over time. In reality, the development of musical instruments may have followed diverse and non-linear paths, and the instruments of one era may have been quite different from those of another, even if they shared the same name.

Iconography

Iconography can be a goldmine for medieval instruments. You can get hints of when and where instruments strutted their stuff, how big they were, how they were played, who was blowing or beating them, and sometimes even what they were made of. But don’t get too comfortable.

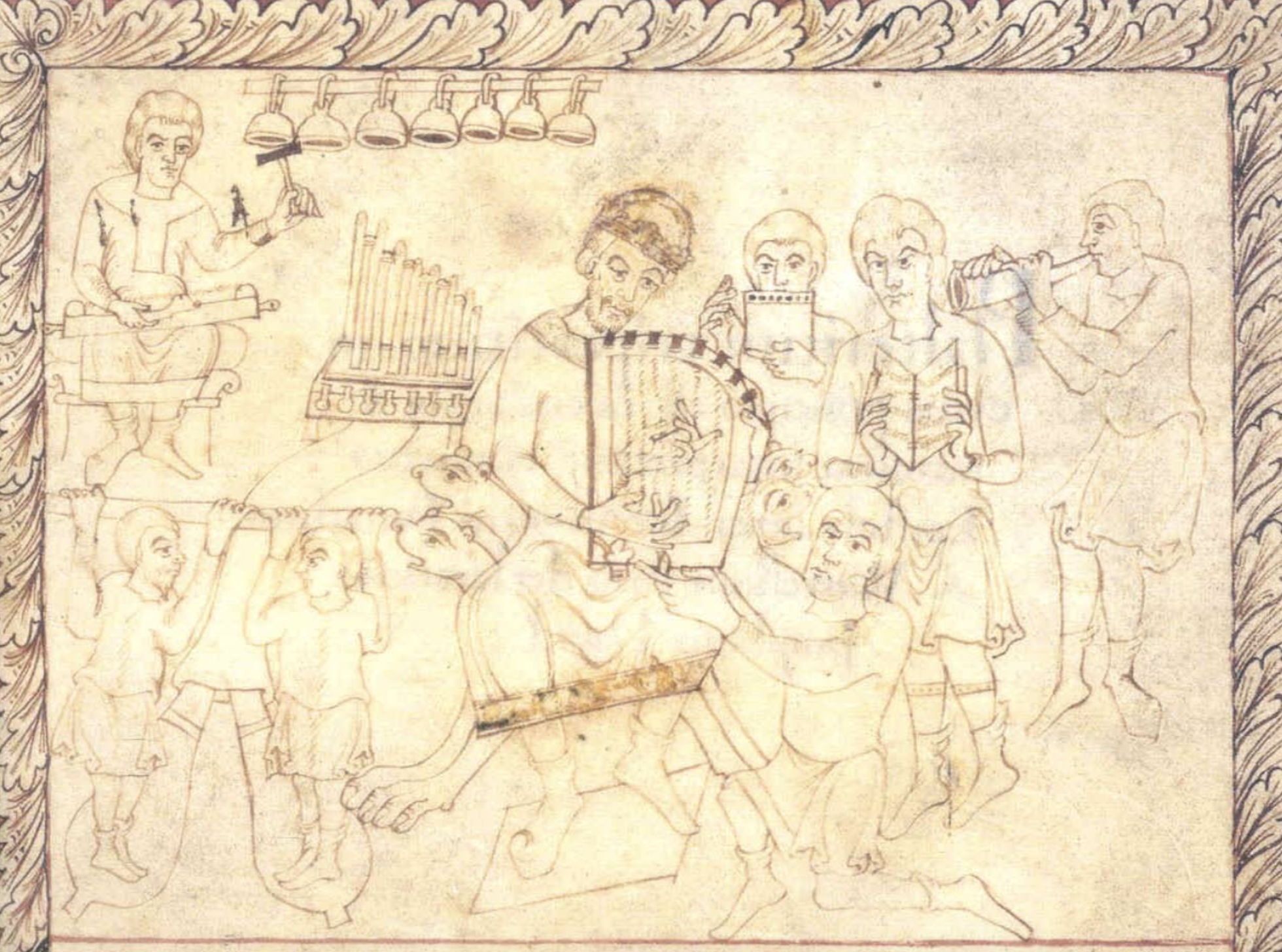

Most of what survives in the iconography department is tied to the church: manuscripts, prayer books, psalters, murals... you get the picture. These works were often expensive and time-consuming to produce, so they're usually religiously flavoured. For example, we often encounter depictions of King David with musicians, which are more symbolic than realistic portrayals of contemporary musical practices.

Iconography has another dirty little secret: artists couldn’t always make instruments look like the real deal. Artists were often limited by the materials available to them (such as stone or wood) and the technology of the time (such as casting methods). This can lead to distortions or impractical representations of instruments. For example, a carving at Chalon-sur-Saône, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, shows a hybrid figure playing a fiddle, but the size of the instrument relative to the figure makes it physically impossible for a human to play. Similarly, the size of instruments in depictions can be difficult to determine, as some representations feature grotesque or mythological creatures whose body proportions may not conform to human norms.

We also face difficulties in determining the materials used to make instruments and their construction details from iconography. It is often unclear what type of material the instrument is made from, how many finger or thumb holes it has, or where they are placed. We may not even be able to tell whether the instrument is a wind instrument, a reed instrument, or a horn. Details such as undercutting of finger holes, the shape and diameter of the bore, or playing techniques, are not depicted.

Were all medieval instruments used in the same way, or did different instruments serve different functions? Were they used solely to produce music, or were they also used for signalling, communication, or ceremonial purposes? In medieval societies, music was deeply entwined with religious, social, and political functions, and the role of the flute, as well as other wind instruments, may have been much more complex than we might assume. In some cases, flutes may have been used in the context of rituals, festivals, or outdoor communication, rather than purely for musical performance. This diversity in usage challenges the modern tendency to categorise instruments based on their function today.

We must also be cautious when we think about medieval flutes as variations of the same instrument. The medieval flute was not a standardised instrument, and it likely varied greatly in design, playing technique, and purpose depending on the region, culture, and specific historical context. To think of medieval flutes as different versions of one archetype may oversimplify the diversity of instruments and musical practices in the Middle Ages.

What Could Actually Be Made

The emergence of the pole lathe in the mid-thirteenth century revolutionised the production of tapering-bored instruments such as shawms and bagpipes. Concurrently, increased mining and the introduction of coal made metals like iron and copper far more accessible, significantly expanding the materials available for instrument-making (Montagu, 2007).

Certain materials naturally lend themselves to the creation of wind instruments. Reed and bamboo are hollow by nature, while animal and bird bones are easily hollowed for use in flutes. Elder (Sambucus nigra), a common European wood, has also been widely used due to its straight growth, dense wood, and soft inner pith, which simplifies boring. Additionally, its abundance made it a practical choice. Flutes crafted from reed, elder, bone, and even rush were prevalent. The Ruspfeife , mentioned by Virdung, translates to calamaula or shepherd’s pipe, highlighting the simplicity and utility of such materials.

Brade (1975) went ferreting about in the archaeological undergrowth and turned up more than a hundred bone flutes from the ninth to sixteenth centuries scattered across Belgium, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. (Leaf, 2008).

Here's what we know: transverse bone flutes didn't exist. Thumb-holes emerged around the twelfth century, though only 5.9% of bone flutes had them, and these thumb-holes appear on mammal bone flutes from the twelfth century onwards.

Many bone flutes were discovered in groups, Most were made from sheep rather than bird bones, which makes sense when you consider that sheep are considerably more gullible and easier to catch . Some flutes even had holes that served no musical purpose but allowed you to hang your flute from your belt.

Bone Flutes as Ancestors of Duct Flutes : The claim that bone flutes are considered ancestors of wooden duct flutes is likely accurate in a general sense, although it's crucial to note the historical development from bone to wood is not definitively established. Bone flutes are usually duct flutes, as opposed to transverse flutes, and it's possible wood was later employed for the same purposes once its properties were better understood and easier to shape. The comparison between bone and wooden instruments could certainly suggest continuity in tradition, but it's important to acknowledge the limited evidence in the transition between these materials. As Leaf (2008) notes, there was a period when bone and wooden instruments coexisted, allowing for comparisons that suggest a continuity of tradition. However, it is important to note bone flutes were typically duct flutes rather than transverse flutes.

Medieval flutes can be broadly categorised into edge-blown and duct-blown types, with four main subcategories:

Panpipes Duct flutes Transverse flutes End-blown flutes

The term flute in the medieval and Renaissance periods was not standardised, and its usage encompassed various types, sounds, and designs. Guillaume de Machaut references instruments such as the flauste brehaingne , floiot de sans , and ele . Literary sources also mention the flajol , flajolet , floyle , frestel , fletsella , muse d’ausay , and estive , with different authorities identifying these as flutes or related wind instruments.

This diversity makes it unlikely all names can be definitively matched to specific types. Flutes in the Middle Ages ranged from simple peasant instruments to sophisticated courtly variants, and their design and use varied significantly by region and culture. Limited travel and communication in the period further contributed to regional differences, while cultural exchanges introduced new ideas and designs, such as Arabic-origin instruments brought to Europe during the Crusades or via Iberia under Moorish influence.

Despite this variety, there was some standardisation in construction methods and materials, as seen in the modern era with Boehm flutes. Though modern instruments exhibit less variation, they still differ in size, material, and features, such as open or closed holes and foot joints. Medieval instruments likely displayed similar diversity within their own contexts.

The Romanesque period marked a shift towards more refined instrument-making, facilitated by technologies like the lathe. Instruments such as bagpipes, shawms, and tabors became more prevalent, often influenced by designs from the Middle East and North Africa.

David Lasocki (2011) notes early duct flutes came in sizes ranging from small to minute, with two to seven holes in various configurations. The one-handed pipe, often paired with a drum (tabor), typically had a thumb-hole and two finger-holes. By the late fourteenth century, a duct flute with a thumb-hole and seven finger-holes emerged, foreshadowing the modern recorder. Lasocki argues the recorder's history must be viewed within the broader family of flutes. I would expand this to include all related instruments, such as tabor pipes, kavals, and panpipes, within this broader framework of flutes in the Middle Ages.

Ultimately, while we can draw insights from historical sources and surviving instruments, much of our understanding of medieval flutes is speculative. Their construction, sound, and use remain subjects of educated guesswork, as modern recreations inevitably interpret rather than replicate the past.

Transverse Flute

The transverse flute, or cross flute, was among the rarest types of flute during the Middle Ages. It likely got its start in India, and early transverse flutes were known in China and Japan, where their presence is documented long before Western noses sniffed it out. The earliest surviving transverse flutes, dating to around 400 BCE, were discovered in the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng in China. These instruments differ from later Chinese and modern flutes, being shorter and having embouchure holes located at a 90-degree angle to the finger holes. Sure, China might have come up with its own versions, but this flute had its passport stamped in India, and spread to China and Japan, where examples from the eighth century AD are preserved in the Shōsōin repository in Nara (Leaf, 2008).

The transverse flute finally sauntered into Europe in the tenth century, making its first continental cameo. These instruments are depicted in Byzantine art, including church psalters and frescoes, such as those in the South Tower of the Hagia Sophia in Kiev, dating from the twelf th century. And what do we see? The flute strutting its stuff next to acrobats and musicians , held to the player’s left rather than the modern right-hand position.

The transverse flute continued its journey into Europe proper, appearing in various medieval manuscripts and artworks. The earliest surviving European representation is an eleventh or twelfth-century cast bronze aquamanile from the National Museum in Budapest. This aquamanile portrays a flautist standing on the back of a centaur, playing a drum. Such depictions suggest the flute was more extensively used in the Holy Roman Empire (roughly modern-day Germany) than elsewhere, earning it the name "German flute" or flûte d’Allemagne . Guillaume de Machaut references the transverse flute in La Prise d’Alexandrie , referring to it as a 'fleuste' or 'fleuthe traversaine' (Leaf, 2008). Similarly, Adenet le Roi’s Cleomadés (c. 1285) descr ibes 'flahutes d’argent traversaines', one of the first unambiguous literary shout-outs.

No medieval transverse flutes made it out of history’s mosh pit intact, leaving us squinting at iconography, scribbled accounts, and comparisons with their later Renaissance cousins. They were probably simple, cylindrical beasts of wood or bone, carved from a single piece. Iconography suggests variations in design, including embouchure holes located either centrally or towards one end of the flute, finger holes anywhere from nada to eight. The absence of thumb holes in medieval depictions suggests their construction might have differed from later designs. For example, the Manessische Liederhandschrift (early 14th century) shows flutes with varying embouchure positions, as seen in Der Kanzler (Cod. Pal. germ. 848, fol. 423v) and Meister Rumslant (fol. 413v). Both images also depict the flute being played alongside a vielle, hinting at their use in ensemble contexts.

One of the flashiest medieval cameos has to be in the Cantigas de Santa Maria , which illustrates two tenor-sized transverse flutes (Madrid, Escorial Monastery, MS b.I.2.). Rudolf von Ems’s Weltchronik (c. 1255–1270), Kauffman’s Haggadah (14th century), and other manuscripts also feature transverse flutes, underscoring their gradual integration into medieval European culture.

Despite these depictions, little is known about the sound, pitch, or playing techniques of medieval transverse flutes. Unlike Renaissance flutes, which were designed for consort performance, medieval flutes were likely solo instruments with thicker walls, wider bores, and larger finger holes. This construction would have contributed to their tonal and technical characteristics. Furthermore, flutes were often associated with pastoral themes, shepherds, and mythological figures like Pan, linking them to rustic and idyllic imagery.

Duct flutes

Duct flutes, aka fipple flutes, are characterised by a design in which the air travels through a wind-way, or duct, onto a sharp edge called the labium. No fancy lip gymnastics required. This feature makes duct flutes particularly accessible, as the player simply needs to blow into the instrument to produce sound. Additionally, duct flutes respond well to a wide variety of articulations. While other flutes often rely on harder articulations to achieve clear speech, duct flutes accommodate both soft and hard articulations with ease.

In contrast, flutes that require an embouchure depend on the player’s lips and facial muscles to shape and adjust the voicing, affecting pitch, tone quality, and dynamics. With duct flutes, the voicing is fixed, which limits their flexibility. A typical characteristic of duct flutes is that blowing harder raises the pitch, resulting in a relatively narrow dynamic range. Fingerings give a bit of wiggle room, but it’s subtle compared to what is achievable with embouchure-formed flutes.

Tilincă

Direct evidence for the tilincă in the Middle Ages is scant, but the ubiquity of duct flutes and the wide territory where the tilincă later pops up makes it damn likely that this little troublemaker was already blowing, squealing, and flirting its way through medieval life. It may not have left a paper trail, but you can bet it was there.

MS 1-2005 f. 188r

The MS 1-2005 Macclesfield Psalter (c. 1330-1340), Folio 188r, depicts a tilincă, although the instrument shown here is not the duct variant. Additionally, the Breviary of France, ca. 1511 (MS M. 8, fol. 150r), also features a possible representation of the tilincă.

The tilincă is essentially a flute without finger-holes; it is a pipe that is either side-blown or, more commonly today, equipped with a duct. It is typically a long flute with a narrow bore, with an approximate length of 75 cm, although shorter versions exist. Longer instruments may require a separate tube or bocal to reach the wind-way, similar to the fujara.

Today, the instrument is found across Central and Eastern Europe, with variations such as the Romanian tilincă, Hungarian tilinkó, Slovak koncovka, Russian kalyuka, and Moldavian csilinko. Similar instruments are also found in other regions, notably the Norwegian seljefløyte.

To play the tilincă, only one finger is needed to open and close the end of the instrument. There are two basic configurations: open and closed. When the instrument is open, it produces the natural overtone series and is often referred to as a harmonic flute. When closed, the instrument functions as a stopped pipe: the air has no escape and travels back the way it entered. Consequently, the airstream becomes approximately twice the length of the open instrument, producing a pitch an octave lower. Once stopped, the tilincă will only produce the odd harmonics of the overtone series. By alternating between the open and closed positions, players can produce a complete scale and play melodies.

Vessel flutes

The tilincă is not the only example of a stopped pipe among duct flutes. Although it is unique in the technique of alternating between open and closed (as far as we know - though given the limited information on playing styles and techniques, it is entirely possible other open flutes employed some method of closing the end while playing), some organ pipes are also closed, as are vessel flutes.

Vessel flutes are among the oldest and most widely distributed types of flutes. The most common vessel flute is the ocarina. The defining characteristic of a vessel flute is that, unlike most flutes, the air does not travel down a tube but instead passes through a vessel. One of the most well-known of these instruments is the gemshorn.

The historical gemshorn was a brief phenomenon during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, and its use was almost entirely confined to Germany. Very little is known about the historical gemshorn, as no reliable surviving examples exist - only a single gemshorn survives today, and it is neither playable nor dated. Interestingly, instruments like the gemshorn, which were once more popular, are now more commonly found in modern use than they were in the past.

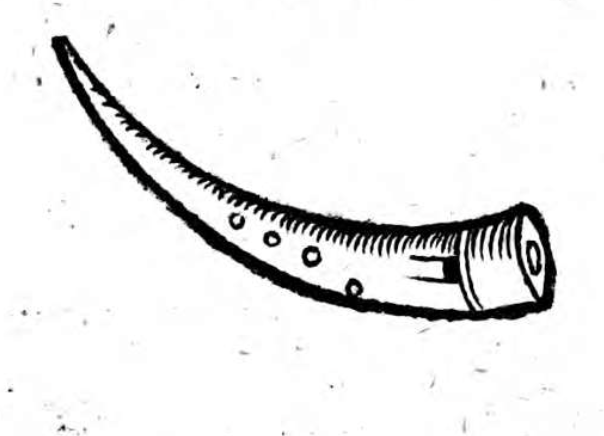

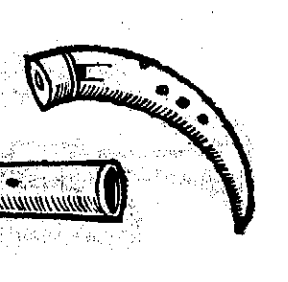

Agricola

The name 'gemshorn' refers to the material from which the instrument is made: goat horn (the modern German term is Gämsen ). A small horn made either from animal horn or metal appears in French sources from the thirteenth century under the name cornet(t) , and the term is found in England in the fifteenth century. Between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, references to cor à doigts in French sources seem to describe horns with finger-holes. These may have been predecessors to the cornetto , perhaps resembling the bukkehorn found today in Norway.

The remarkable feature of the gemshorn is that it is a vessel flute, which is unique in being a horn played by blowing at the wide end of the horn, unlike a hunting horn where the narrow end is blown.

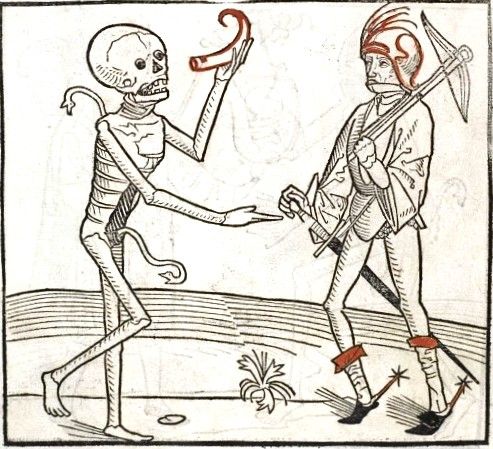

The gemshorn appears in a few iconographical specimens, notably in the woodcuts of the Heidelberger Totentanz (Dance of Death) from 1488. These woodcuts depict a personification of Death playing or holding various musical instruments, including the lute, bray harp, shawm, tromba marina, bagpipe, psaltery, and more. One woodcut clearly depicts a gemshorn with the window (the rectangular hole near the mouthpiece) visible, and this instrument is played at the wide end, as expected for a gemshorn. Although the illustration lacks finger-holes, this depiction places the earliest recorded date for the gemshorn at 1488. This illustration is unique in that it shows the gemshorn without finger-holes.

Virdung (1511) depicts the gemshorn with four finger-holes. Although the presence of four finger-holes rather than eight does not necessarily reduce the compass of the instrument compared to a nine- or eight-holed instrument, it is worth noting that the difference in finger-holes did not significantly limit its range.

The gemshorn was also depicted in Dürer’s Prayerbook for Emperor Maximilian (1515), further cementing its place in the late medieval to Renaissance musical landscape.

In the context of the pipe organ, there are various stops used to admit air into different ranks (groups) of pipes. One such stop is called gemshorn (in English and German), Gemshoorn (in Dutch), and Cor de Chamois (in French). The pipes of the gemshorn organ stop are not stopped at the end, as with a true gemshorn or other stopped pipes such as the Gedackt , Bourdon , or Stopped Diapason . Instead, the gemshorn organ stop pipes have an inverted conical shape.

The earliest known gemshorn organ stop dates from the early sixteenth century.

The gemshorn was played from the late fourteenth century to the middle of the sixteenth century, and its use is further documented by another German musician and musical lexicographer, Michael Praetorius, who provided diagrams of the gemshorn in his De Organographia .

After this, the gemshorn disappears from the historical records. It appears extremely rarely in any known documents or iconography and is found only in Germany. Furthermore, no music was written specifically for it, which, although typical for medieval instruments, is a significant omission for the Renaissance period. As a result, we must conclude that the gemshorn was a very minor player in Renaissance and early Baroque music. It was never used in mainstream music of the period. Despite some early music ensembles using it for medieval music, there is no evidence of its existence or use in the Middle Ages before 1455, which could be considered the beginning of the Renaissance. Some shops sell gemshorn consorts - a set in different sizes and therefore at different pitches - for which there is no historical evidence. These modern reproductions often include seven finger-holes on the front and one on the back, allowing them to be played like recorders. Thus, the gemshorn remains an early music curiosity, with an uncertain repertoire and unclear historical use, though it possesses a haunting and lovely sound.

Today, the gemshorn has been recreated with eight finger-holes, allowing it to be played like a recorder, although it still has a limited range of only a ninth. Instruments are now being produced in various sizes and consorts. However, the historical evidence for the gemshorn remains scarce, and there is no evidence of its use in consorts during the Renaissance.

Five and Six-Hole Pipes

The number of finger-holes a flute has determines how many fundamental pitches can be played before the break to the first overtone occurs. For example, with three holes, a full octave can be played. The kaval occupies a somewhat unique position with five finger-holes, similar to the shakuhachi, though the shakuhachi features a thumb-hole, while the kaval has all its holes on the front.

The term 'kaval' is commonly thought to originate from the Arabic root q-w-l (kalima, kalām ), meaning 'to speak.' A modern word derived from this root is qawwal , meaning 'an itinerant musician.' It is also possible that the term derives from kav/kov ('hollow'), which is comparable with the Latin tibia, referring to the aulos ( αὐλός) . The term tibia also reappeared in the Middle Ages, together with fistula , referring to musical instruments. Therefore, there are possibilities that the term kaval derives from the aulos: kavalos, kavlos, khaulos .

The Maramureș term for the kaval is fluer lung or fluer mare in Romanian (with caval or kaval being the older Romanian term), kaval or kawal in Bulgarian, furugla or hosszú furulya / hosszúfurulya ('long flute') in Hungarian, and кавал in Russian. In Romania, the kaval typically refers to a long duct flute with five finger-holes in groups of two (low) and three (high), found in regions such as Oltenia, Muntenia, and southern Moldavia.

There is a traditional style of playing the kaval among the Hungarian Csángó minorities in Moldavia, where players sing or growl a low drone while playing the flute. This style creates a third tone, known as the difference tone, which can be distinctly heard.

Another type of kaval is the duct flute found in Hungary and Romania . Such instruments may have been more widely distributed throughout the Balkans but were eventually overtaken by the edge-blown kaval. The duct variety typically features five finger-holes and is still found in regions such as Oltenia, Muntenia, and southern Moldavia, where the traditional style of playing with a low drone continues.

In Slovakia, several types of edge-blown flutes are known, such as the lupštik and the kosá č ik . Little is known about the kosá č ik , but Karol Kočík mentions that it originates from the Liptov region, with Ján Plieštik from Lučatín being famous for producing them. The lupštik , on the other hand, is made from caraway (Carum carvi L.), a hard dried plant stem. This instrument does not have finger-holes and is played similarly to the tilinca or koncovka. Other edge-blown flutes in Slovakia and Central Europe, such as the Slovak pistalka , are increasingly rare and are being overtaken by the more popular and accessible duct flutes.

Low Recorders Before 1511

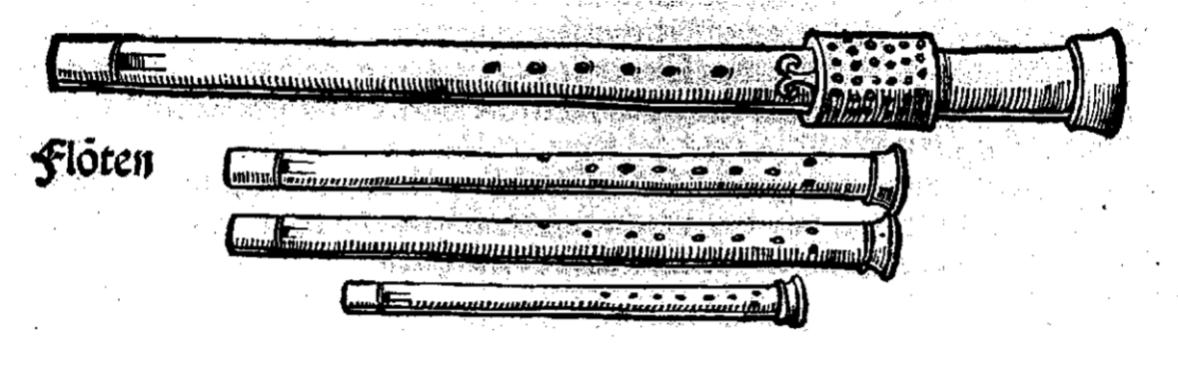

“When we search for the beginnings of the true recorder, with its thumb hole and seven finger holes, as distinct from the various folk pipes—mostly six-holed—from which it evolved, it is not long before we find the bass recorder side by side with trebles and tenors. It is as if the musicians of the Renaissance, tired of the high pitch of the available folk pipes of the Middle Ages, sought the depth and mellowness of larger instruments to form a wind group comparable to the consort of viols. The evidence seems to point to Italy as the birthplace of the recorder, probably towards the end of the fourteenth century. Be that as it may, the earliest surviving reference book on musical instruments, Sebastian Virdung’s Musica Getutscht (1511), shows the trio of recorders: treble (g’), tenor (c’), and bass (f), and includes a table of fingerings in which the bass is given a range of an octave and a sixth” (Hunt, 1975).

Due to the difficulty in construction, the extended length, the need for keys to make the stretch possible, and the use of a bocal, it is not generally thought that recorders lower than the tenor existed until the Renaissance, nor is there reason to believe that they existed before Virdung’s Musica Getutscht of 1511, which is generally regarded as the first mention of them.

Flöten as depicted by Virdung

“No one knows when the bass recorder was invented, but it seems to have been developed in the late fifteenth century. At that time, instrument makers began to build consorts of like instruments in various sizes to correspond with vocal ranges, in order to play vocal music in the new imitative polyphonic style” (Primus, 1984, p. 101).

Such instruments as Virdung described were certainly in use at the time, and an example can be found in Pierre Attaingnant’s 1533 Parisian chansons, where he specified certain pieces as suitable for recorder quartets, all of which could be played using Virdung’s instrumentation (Primus, 1984, p. 101).

But were bass recorders in use before this time? The earliest surviving recorders date from the sixteenth century and are now housed at the Accademia Filarmonica in Bologna (Paalman, 2009). Additionally, five archaeological finds date from the fourteenth century, though no fifteenth-century instruments have survived. However, several sources point to the use of bass recorders in the fifteenth century: 'Historische bronnen maken aannemelijk dat een blokfluitconsort in het midden van de vijftiende eeuw in Europa een wijdverbreid verschijnsel was' (Hijmans, 2015).

Notable research on the recorder consort in the fifteenth century has been conducted by Ita Hijmans, Aventure, and Filling the Gap , suggesting that the Dordrecht recorder is part of a developing oral tradition linked with the monophonic song tradition of Oswald von Wolkenstein, Mönch von Salzburg, and the Gruuthuse collection, which flourished around 1400 (Hijmans, 2016).

“Afbeeldingen en archivalische bronnen uit de late Middeleeuwen doen vermoeden dat instrumentalisten en instrumentale ensembles een belangrijke rol speelden in de maatschappij. Tegelijkertijd is schriftelijk overgeleverd muziekrepertoire uit die periode, dat eenduidig bedoeld was voor instrumentaal ensemble, zeer schaars. Instrumentalisten lijken niet primair afhankelijk te zijn geweest van schriftelijk materiaal. Zij maakten hun eigen instrumentale versies van vocale modellen. Het ontrafelen van het proces dat ten grondslag zou kunnen liggen aan de uitvoeringspraktijk van instrumentale ensembles in het vijftiende-eeuwse Europa ten noorden van de Alpen kan ons wellicht de weg wijzen” (Hijmans, 2014).

With the earliest known depiction and unambiguous reference to the recorder consort being found in the early sixteenth century, and surviving medieval instruments from the fourteenth century, Ita Hijmans and Filling the Gap literally fill the gap on what consort recorders might have existed in the fifteenth century, and their possible repertoire (Primus, 1984, p. 101).

“Hijmans begins by reminding us that ‘Very few recorders from the first decades of the sixteenth century still exist, and none survive from the fifteenth century’ (except for the ‘archeological finds from around 1400’). So to gather information about what recorders were like in the period 1470-1520, she looked at visual representations of the instrument in four geographic areas. Generally speaking, recorders in German-influenced areas were wider (as reflected in the later extant instruments by the Rauchs and Schnitzers), those from Flanders and France narrower (as reflected in instruments by Rafi), and those from northern Italy mixed: narrow and slightly wider, in keeping with ‘the appearance of many German instrumentalists and Flemish musicians in the Italian cultural centers.’ Treatises ‘appear from the middle of the fifteenth century, mentioning the recorder, explaining the consort idea, expressing the new concept of instrumental music, and finally describing the sizes of the recorder family....’ Since no repertoire is indicated as being for recorders in the period in question, she comes up with possible answers to what recorder consorts would have played from the Glogau manuscript, the Casanatense manuscript, and Fridolin Sicher’s songbook, then presents a case study of Brussels II 270 (a songbook originating in the Northern Netherlands)” (Griscom & Lasocki, 2013, p. 395).

The bass recorder in F, called Baßcontra or Bassus by Virdung (Agricola used the latter), appears to have been the terminology used for the instrument lower than the tenor. Ganassi (1535) describes three sizes of recorder: soprano (g’), tenor (c’) and basso (f), which correspond exactly to Virdung's terms.

It was not until 1619, when Praetorius in Syntagma Musicum II (Wolfenbüttel, 1619) described a gans Stimmwerck or Accort (whole consort), that the terminology evolved. Due to the extended range of these instruments, Praetorius had to rename all but the tenor and switch to 8’ pitch as sounding: Groß-baß in F, Baß in Bb, Basset in f, etc. In the twentieth century, the size in F was generally called a bass recorder. However, as lower recorders have become more common, we now use Praetorius’ terminology and refer to that size as a basset . This would suggest that no instrument larger than what Praetorius called a basset existed until the latter half of the sixteenth century. (Brown & Lasocki, 2006, p. 23)

The earliest surviving recorder specimens date from the fourteenth century, including the Dordrecht recorder, the Göttingen recorder, the Tartu recorder, and the Esslingen recorder. These instruments, along with other surviving whistles and pipes, are of soprano/alto sizes, and Virdung's description is taken as a representation of the bass recorder's development toward the end of the fifteenth century.

This work serves as a starting point to explore the possibility of the bass recorder in music predating Virdung, consulting art and literature as primary sources that point towards the use of the bass recorder in the medieval period. While there has been a significant amount of research conducted on the subject of early bass recorders, notably by Adrian Brown and David Lasocki, the instruments used in the medieval period have not been examined in great detail. The purpose here is to present the evidence suggesting the existence of a medieval bass recorder, to guide the reader interested in the instrument, and to offer some ideas and suggestions for further research in this area.

Literary References

“Tinctoris’ traktaat, dat mogelijk al uit 1472 dateert, geeft ook informatie over ensemblespel op blaasinstrumenten die van ongelijke grootte, maar van dezelfde familie zijn. Hij legt uit dat erzangerszijn die hoog, laag of midden zingen in composities. Naar voorbeeld van de standaard van de menselijke stem worden de blaasinstrumenten ook suprema(of discant), tenor en contratenor genoemd.” (Paalman, 2009)

In medieval literature, there was no specific term for each individual type of flute: terms such as flauste , floiot de saus , ele , flajolet , floyle , frestel , fletsella , muse d’ausay , estiva , and many others were used to denote wind instruments. However, the name alone does not reveal the exact nature of the instrument. This was a time when instruments existed in many forms, with a wide range of regional styles and variations, from simple peasant instruments to those of high sophistication. A glance at modern folk music today provides an idea of this variety: from the sopilka of Ukraine to the tilinko of Hungary, the shvi in Armenia, the Bulgarian kaval , and the many unique whistles found in Transylvania. The list goes on, and there is hardly a country that does not have its own specific type of whistle unique to that region. In this sense, the notion of a recorder as we know it today in the fifteenth century or earlier is somewhat anachronistic. What we may find are regional pipes, which could be considered recorders only in the sense that they have a thumb hole and seven finger holes.

The purpose here is to highlight literary examples that reference a lower recorder, in order to suggest that such instruments did indeed exist. While the literature is often vague, there is some evidence to indicate the existence of the instrument prior to 1511. However, comprehensive documentation of these references remains a gap in the research on the instrument, with mentions being rare, and until the Renaissance, scarcely existent.

For example, in 1410, we find the inventory of Juan of Catalunya, which suggests the presence of a recorder consort. The inventory lists: ' tres flautes, dues grosses e una negra petita' (two flautes: two large and one small black one). This is one of the earliest references to the recorder, predating the recorder in England by a decade, and suggests that these instruments were used for three-part consort music. (Lasocki, 2011)

Guillaume Machaut’s epic poem La Prise d’Alexandrie , written toward the end of his life (c. 1370-72), mentions at least twenty types of flajols (three-hole pipes), both loud and soft. In his earlier Le remède de Fortune (c. 1340s?), he had already singled out flajos de sans (flajols made of willow). (Lasocki, 2011)

Archival records for fleustes / flustes (plural) at the Court of Burgundy date back as early as 1383. In 1426 and 1443, the duke ordered sets of four recorders; in 1454, four minstrels performed on recorders; and in 1468, four minstrels almost certainly played a four-part chanson on recorders. In Brescia, Italy, in 1408, a pifaro (wind player) of the count ordered four new flauti . In France, in 1416, the queen ordered eight grans fleustes and a case for five of them. The adjective "large" suggests these may have been discants (and possibly lower sizes), rather than sopranos. Bruges is the earliest documented city band to have ordered a case of recorders ( fleuten ) in 1481-82, and the presence of four minstrels in the band strongly suggests that the case contained a set of four recorders. The recurring theme of "four" indicates that recorders were commonly used for the four-part polyphonic music that was already being composed in the late 14th century and became more developed from the 1430s onwards. (Lasocki, 2011)

Iconography

While the literary evidence alone does not entirely support the argument that the bass recorder was in use for a significant period before the sixteenth century, the iconographic evidence provides several compelling sources that strongly suggest the early use of the bass recorder. The earliest known depiction dates from the 11th century, found in the carved stone pillar at Bourbon-l'Archambault in Burgundy. This depiction shows a musician playing a pipe-and-tabor-like instrument, while other players are shown with a rebec or fiddle. A third musician is depicted playing a flute, with the left-hand thumb positioned in such a way as to indicate the presence of a thumb-hole, which is consistent with the design of a recorder.

Additionally, in the early fourteenth-century Ormesby Psalter , housed in the Bodleian Library, there is an illumination featuring an image of a cockerel/man playing a large pipe.

Another fourteenth-century depiction may be found in Spain: at the Catedral El Salvabori , an angel is shown playing a large-sized flute.

A more significant find, from approximately the same time as the double pipes in France, is a depiction of an animal (presumably a bear, though possibly a monkey) playing a recorder. This is carved into a wooden bench at St. German’s Church, Wiggenhall, Norfolk, England. This church is renowned for its exceptional examples of late medieval woodwork. There are two points of interest in this image: first, the instrument clearly has double holes for the little finger; second, the instrument appears to have a bent head, resembling today's 'knick' instruments.

Not far from Wiggenhall, an early fifteenth-century carved roof beam is located in the chapel of St. Nicholas in King's Lynn. The carving depicts an angel playing a larger recorder, possibly a tenor or larger size, although alterations may have been made during the Victorian period.

Perhaps the most eyebrow-raising, chair-leaning, finger-pointing piece of evidence for an early bass recorder comes from the late fifteenth century in Girona Cathedral (likely between 1486 and 1506). Here, two silver angels are depicted: one playing a tenor or basset recorder, and the other playing a bass recorder with a bocal. The presence of the bocal this early is particularly remarkable, suggesting that the instrument had already undergone some development by this time. This is the earliest known unambiguous depiction of a bass recorder, and it is also the first known depiction of a bocal on the recorder, dating from the fifteenth century.

A Pipe out of place

The frestel, medieval Europe’s answer to the panpipe, held the iconographic high ground for a good three centuries before vanishing around 1300.

Fashioned from boxwood, with neatly convex ends and a monoxyle construction, this single-handed marvel found itself equally at home on cathedral portals and skulking in the margins of manuscripts.

The frestel quietly lost its place. What remains is a single archaeological specimen and a handful of stone and painted representations, collectively staring back at us.

The Sound of one hand piping

This ingenious contraption exploded across Europe in the mid-thirteenth century. One moment it barely existed; the next, manuscripts from England to Spain were depicting the same curious instrument combination.

Every region claimed it with a different name: the galoubet in sun-drenched Provence, the Schwegel in German-speaking lands, the txistu in the Basque hills. But the appeal was universal. Need music for a Burgundian tournament? Pipe and tabor. Street festival in a Spanish town square? Pipe and tabor. Shakespeare's Globe Theatre needed atmospheric sound effects? You guessed it.