Low Recorders Before 1511

Benji Rose

2020

Angel Musician (ca 1415), England. King’s Lynn: Chapel of St Nicholas, carved chestnut-wood roof beam ("Anonymous 15th Century." Recorder Homepage, www.recorderhomepage.net/recorder-iconography/anonymous-15th-century/. Accessed 01.05.2019).

Introduction

“When we search for the beginnings of the true recorder, with its thumb hole and seven finger holes, as distinct from the various folk pipes—mostly six-holed—from which it evolved, it is not long before we find the bass recorder side by side with trebles and tenors. It is as if the musicians of the Renaissance, tired of the high pitch of the available folk pipes of the Middle Ages, sought the depth and mellowness of larger instruments to form a wind group comparable to the consort of viols. The evidence seems to point to Italy as the birthplace of the recorder, probably towards the end of the fourteenth century. Be that as it may, the earliest surviving reference book on musical instruments, Sebastian Virdung’s Musica Getutscht (1511), shows the trio of recorders: treble (g’), tenor (c’), and bass (f), and includes a table of fingerings in which the bass is given a range of an octave and a sixth” (Hunt, 1975).

Due to the difficulty in construction, the extended length, the need for keys to make the stretch possible, and the use of a bocal, it is not generally thought that recorders lower than the tenor existed until the Renaissance, nor is there reason to believe that they existed before Virdung’s Musica Getutscht of 1511, which is generally regarded as the first mention of them.

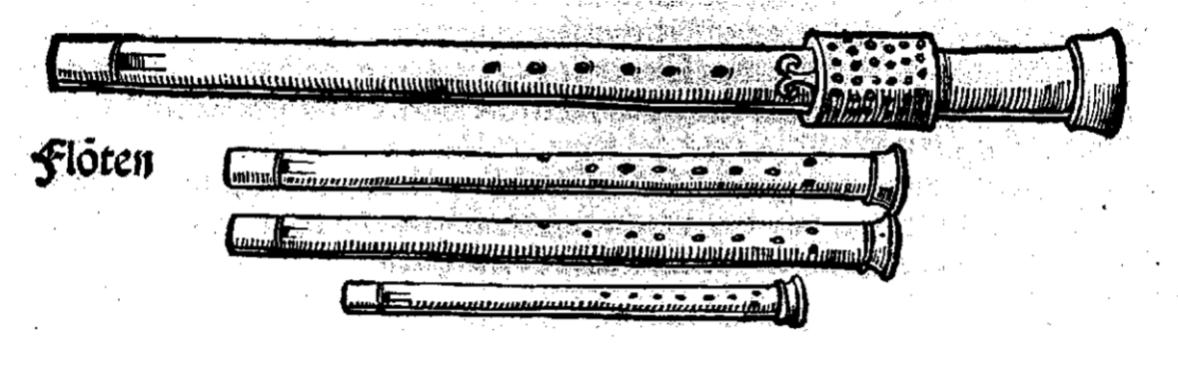

Flöten as depicted by Virdung

“No one knows when the bass recorder was invented, but it seems to have been developed in the late fifteenth century. At that time, instrument makers began to build consorts of like instruments in various sizes to correspond with vocal ranges, in order to play vocal music in the new imitative polyphonic style” (Primus, 1984, p. 101).

Such instruments as Virdung described were certainly in use at the time, and an example can be found in Pierre Attaingnant’s 1533 Parisian chansons, where he specified certain pieces as suitable for recorder quartets, all of which could be played using Virdung’s instrumentation (Primus, 1984, p. 101).

But were bass recorders in use before this time? The earliest surviving recorders date from the 16th century and are now housed at the Accademia Filarmonica in Bologna (Paalman, 2009). Additionally, five archaeological finds date from the 14th century, though no 15th-century instruments have survived. However, several sources point to the use of bass recorders in the 15th century: "Historische bronnen maken aannemelijk dat een blokfluitconsort in het midden van de vijftiende eeuw in Europa een wijdverbreid verschijnsel was" (Hijmans, 2015).

Notable research on the recorder consort in the 15th century has been conducted by Ita Hijmans, Aventure, and Filling the Gap, suggesting that the Dordrecht recorder is part of a developing oral tradition linked with the monophonic song tradition of Oswald von Wolkenstein, Mönch von Salzburg, and the Gruuthuse collection, which flourished around 1400 (Hijmans, 2016).

“Afbeeldingen en archivalische bronnen uit de late Middeleeuwen doen vermoeden dat instrumentalisten en instrumentale ensembles een belangrijke rol speelden in de maatschappij. Tegelijkertijd is schriftelijk overgeleverd muziekrepertoire uit die periode, dat eenduidig bedoeld was voor instrumentaal ensemble, zeer schaars. Instrumentalisten lijken niet primair afhankelijk te zijn geweest van schriftelijk materiaal. Zij maakten hun eigen instrumentale versies van vocale modellen. Het ontrafelen van het proces dat ten grondslag zou kunnen liggen aan de uitvoeringspraktijk van instrumentale ensembles in het vijftiende-eeuwse Europa ten noorden van de Alpen kan ons wellicht de weg wijzen” (Hijmans, 2014).

With the earliest known depiction and unambiguous reference to the recorder consort being found in the early 16th century, and surviving medieval instruments from the 14th century, Ita Hijmans and Filling the Gap literally fill the gap on what consort recorders might have existed in the 15th century, and their possible repertoire (Primus, 1984, p. 101).

“Hijmans begins by reminding us that ‘Very few recorders from the first decades of the sixteenth century still exist, and none survive from the fifteenth century’ (except for the ‘archeological finds from around 1400’). So to gather information about what recorders were like in the period 1470-1520, she looked at visual representations of the instrument in four geographic areas. Generally speaking, recorders in German-influenced areas were wider (as reflected in the later extant instruments by the Rauchs and Schnitzers), those from Flanders and France narrower (as reflected in instruments by Rafi), and those from northern Italy mixed: narrow and slightly wider, in keeping with ‘the appearance of many German instrumentalists and Flemish musicians in the Italian cultural centers.’ Treatises ‘appear from the middle of the fifteenth century, mentioning the recorder, explaining the consort idea, expressing the new concept of instrumental music, and finally describing the sizes of the recorder family....’ Since no repertoire is indicated as being for recorders in the period in question, she comes up with possible answers to what recorder consorts would have played from the Glogau manuscript, the Casanatense manuscript, and Fridolin Sicher’s songbook, then presents a case study of Brussels II 270 (a songbook originating in the Northern Netherlands)” (Griscom & Lasocki, 2013, p. 395).

The bass recorder in F, called Baßcontra or Bassus by Virdung (Agricola used the latter), appears to have been the terminology used for the instrument lower than the tenor. Ganassi (1535) describes three sizes of recorder: soprano (g’), tenor (c’) and basso (f), which correspond exactly to Virdung's terms.

It was not until 1619, when Praetorius in Syntagma Musicum II (Wolfenbüttel, 1619) described a gans Stimmwerck or Accort (whole consort), that the terminology evolved. Due to the extended range of these instruments, Praetorius had to rename all but the tenor and switch to 8’ pitch as sounding: Groß-baß in F, Baß in Bb, Basset in f, etc. In the 20th century, the size in F was generally called a bass recorder. However, as lower recorders have become more common, we now use Praetorius’ terminology and refer to that size as a basset. This would suggest that no instrument larger than what Praetorius called a basset existed until the latter half of the 16th century. However, for the sake of convenience in this work, bass will refer to any recorder lower than the tenor. (Brown & Lasocki, 2006, p. 23)

The earliest surviving recorder specimens date from the 14th century, including the Dordrecht recorder, the Göttingen recorder, the Tartu recorder, and the Esslingen recorder. These instruments, along with other surviving whistles and pipes, are of soprano/alto sizes, and Virdung’s description is taken as a representation of the bass recorder’s development toward the end of the 15th century.

This work serves as a starting point to explore the possibility of the bass recorder in music predating Virdung, consulting art and literature as primary sources that point towards the use of the bass recorder in the medieval period. While there has been a significant amount of research conducted on the subject of early bass recorders, notably by Adrian Brown and David Lasocki, the instruments used in the medieval period have not been examined in great detail. The purpose here is to present the evidence suggesting the existence of a medieval bass recorder, to guide the reader interested in the instrument, and to offer some ideas and suggestions for further research in this area.

Literary References

“Tinctoris’ traktaat, dat mogelijk al uit 1472 dateert, geeft ook informatie over ensemblespel op blaasinstrumenten die van ongelijke grootte, maar van dezelfde familie zijn. Hij legt uit dat erzangerszijn die hoog, laag of midden zingen in composities. Naar voorbeeld van de standaard van de menselijke stem worden de blaasinstrumenten ook suprema(of discant), tenor en contratenor genoemd.” (Paalman, 2009)

In medieval literature, there was no specific term for each individual type of flute: terms such as flauste, floiot de saus, ele, flajolet, floyle, frestel, fletsella, muse d’ausay, estiva, and many others were used to denote wind instruments. However, the name alone does not reveal the exact nature of the instrument. This was a time when instruments existed in many forms, with a wide range of regional styles and variations, from simple peasant instruments to those of high sophistication. A glance at modern folk music today provides an idea of this variety: from the sopilka of Ukraine to the tilinko of Hungary, the shvi in Armenia, the Bulgarian kaval, and the many unique whistles found in Transylvania. The list goes on, and there is hardly a country that does not have its own specific type of whistle unique to that region. In this sense, the notion of a recorder as we know it today in the 15th century or earlier is somewhat anachronistic. What we may find are regional pipes, which could be considered recorders only in the sense that they have a thumb hole and seven finger holes.

The purpose here is to highlight literary examples that reference a lower recorder, in order to suggest that such instruments did indeed exist. While the literature is often vague, there is some evidence to indicate the existence of the instrument prior to 1511. However, comprehensive documentation of these references remains a gap in the research on the instrument, with mentions being rare, and until the Renaissance, scarcely existent.

For example, in 1410, we find the inventory of Juan of Catalunya, which suggests the presence of a recorder consort. The inventory lists: "tres flautes, dues grosses e una negra petita" (two flautes: two large and one small black one). These instruments may have included those bought for the Infante in 1378. In any case, they appear to form a set of three instruments in two different sizes—likely suited to playing three-part consort music of the time. This is one of the earliest references to the recorder, predating the recorder in England by a decade, and suggests that these instruments were used for three-part consort music. (Lasocki, 2011)

The Court of Burgundy purchased sets of four recorders in 1426 and 1443, around the same time that the Court composer Gilles Binchois began composing four-part chansons, such as Les Filles à marier, which dates from the 1430s. The royal minstrel Verdelet, a celebrated player of the flajolet (possibly the flute or recorder), died in 1436. Flustes were played at the Court in settings that strongly suggest the use of sets of recorders. For example, at a grand banquet in 1454, "four minstrels with fleutres played most melodiously." Fourteen years later, at a royal wedding, “four wolves with flustes in their paws began to play a chanson.” The wolves were followed by four singers who "sang a chanson in four parts." Therefore, it is likely that the wolves played a four-part chanson on recorders. (Lasocki, 2012)

Guillaume Machaut’s epic poem La Prise d’Alexandrie, written toward the end of his life (c. 1370-72), mentions at least 20 types of flajols (three-hole pipes), both loud and soft. In his earlier Le remède de Fortune (c. 1340s?), he had already singled out flajos de sans (flajols made of willow). (Lasocki, 2011)

Archival records for fleustes/flustes (plural) at the Court of Burgundy date back as early as 1383. In 1426 and 1443, the duke ordered sets of four recorders; in 1454, four minstrels performed on recorders; and in 1468, four minstrels almost certainly played a four-part chanson on recorders. In Brescia, Italy, in 1408, a pifaro (wind player) of the count ordered four new flauti. In France, in 1416, the queen ordered eight grans fleustes and a case for five of them. The adjective "large" suggests these may have been discants (and possibly lower sizes), rather than sopranos. Bruges is the earliest documented city band to have ordered a case of recorders (fleuten) in 1481-82, and the presence of four minstrels in the band strongly suggests that the case contained a set of four recorders. The recurring theme of "four" indicates that recorders were commonly used for the four-part polyphonic music that was already being composed in the late 14th century and became more developed from the 1430s onwards. (Lasocki, 2011)

Iconography

While the literary evidence alone does not entirely support the argument that the bass recorder was in use for a significant period before the 16th century, the iconographic evidence provides several compelling sources that strongly suggest the early use of the bass recorder. The earliest known depiction dates from the 11th century, found in the carved stone pillar at Bourbon-l'Archambault in Burgundy. This depiction shows a musician playing a pipe-and-tabor-like instrument, while other players are shown with a rebec or fiddle. A third musician is depicted playing a flute, with the left-hand thumb positioned in such a way as to indicate the presence of a thumb-hole, which is consistent with the design of a recorder.

Additionally, in the early 14th-century Ormesby Psalter, housed in the Bodleian Library, there is an illumination featuring an image of a cockerel with the body of a man playing a large pipe. If this pipe is indeed a recorder, it would likely represent a bass recorder, given its size. (http://www.recorderhomepage.net/recorder-iconography/anonymous-pre-14th-century/ Accessed 01.05.2019)

Another 14th-century depiction may be found in Spain: at the Catedral El Salvabori, an angel is shown playing a large-sized flute. (http://www.recorderhomepage.net/recorder-iconography/anonymous-14th-century/ Accessed 01.05.2019)

In 14th-century France, a depiction of an ensemble includes a harp, bagpipe, a possible recorder, and two double pipes, one of which is notably long. Unlike other depictions, this image does not necessarily suggest a low instrument. Instead, it could represent a tabor-pipe-type instrument, similar to those seen in the Sforza Hours (1490-1521), a famous Book of Hours. Interestingly, this depiction does not feature a low recorder, although it includes a variety of other instruments such as the hurdy-gurdy, pipe and triangle, and fiddle. The significance of the long pipes depicted here lies in the fact that they show the means for constructing low instruments was available in the 15th century. While the spacing of the finger holes on such instruments might have posed a challenge without keys, this does not necessarily invalidate the presence of low pipes before the 16th century. (http://www.recorderhomepage.net/recorder-iconography/anonymous-14th-century/ Accessed 01.05.2019)

There is one exception from the Sforza Hours that might suggest a low recorder. In the depiction of a choir of angels playing various instruments, two angels on either side are shown playing trumpets. On one side, there is a double pipe, and on the other, a long pipe with finger-holes. It is unclear whether this instrument is a cornett or a recorder. There is a possibility that the puffed cheeks suggest a brass instrument; however, this is not the case for many of the other wind instruments, which do not require such pressure, except for the panflute. The panflute, unlike the double pipe and bagpipe, does require a certain embouchure, but its depiction, with what appear to be windows (possibly finger-holes), and the position of the player’s hands, may indicate duct flutes instead.

A more significant find, from approximately the same time as the double pipes in France, is a depiction of an animal—presumably a bear, though possibly a monkey—playing a recorder. This is carved into a wooden bench at St. German’s Church, Wiggenhall, Norfolk, England. This church is renowned for its exceptional examples of late medieval woodwork. It is worth noting that all the carvings are somewhat eccentric, and the location of the church at a port town could be significant in terms of the outside influences on these carvings and the objects they depict. There are two points of considerable interest in this image: first, the instrument clearly has double holes for the little finger; second, the instrument appears to have a bent head, resembling today’s ‘knick’ instruments. While the existence of such ‘knick’ instruments in the late medieval period seems unlikely, it is more plausible that the bent shape was a result of convenience or practicality in the carving.

Not far from Wiggenhall, an early 15th-century carved roof beam, as seen on the title page, is located in the chapel of St. Nicholas in King’s Lynn. The carving depicts an angel playing a larger recorder, possibly a tenor or larger size, although alterations may have been made during the Victorian period. (http://www.recorderhomepage.net/recorder-iconography/anonymous-15th-century/ Accessed 01.05.2019)

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for an early bass recorder comes from the late 15th century in Girona Cathedral (likely between 1486 and 1506). Here, two silver angels are depicted—one playing a tenor or basset recorder, and the other playing a bass recorder with a bocal. The presence of the bocal this early is particularly remarkable, suggesting that the instrument had already undergone some development by this time. This is the earliest known unambiguous depiction of a bass recorder, and it is also the first known depiction of a bocal on the recorder, dating from the 15th century. (http://www.recorderhomepage.net/recorder-iconography/anonymous-15th-century/ Accessed 01.05.2019)

Conclusion

There is substantial evidence suggesting that bass recorders were known before Virdung’s time, and the depiction of a recorder with a bocal in the 15th century is an especially early discovery. This points to the likely existence of bass pipes before the 16th century. The two angels depicted in Girona Cathedral (c. 1486-1506), one playing a tenor/basset recorder and the other a bass recorder with a bocal, provide some of the most compelling evidence for the existence of bass recorders in the late 15th century.

However, caution is needed when interpreting early iconographic depictions, such as the 11th-century David and the Psalmists, as they may not fully represent the instruments used at the time. While literary sources do not explicitly mention bass recorders, they do refer to wind instruments being used in consorts, which supports the idea of low-pitched instruments being part of early ensemble music.

The examination of medieval artwork reveals the wide variety of musical instruments used in the period, and although artistic representations may have involved some creative liberties, they provide valuable insight into the types of instruments that may have been in use. While surviving instruments are rare, the literary and visual evidence suggests that low-pitched wind instruments, potentially bass recorders, were part of the musical landscape long before Virdung's time.

Although no single, definitive piece of evidence conclusively proves the early existence of bass recorders, the combined sources of archival records, iconography, and surviving music strongly suggest that bass recorders—or similar low pipes—existed well before 1511. Further research into medieval instruments, particularly in the context of pre-16th-century Europe, is needed to uncover more evidence of the early use of bass recorders and to better understand the complexity of medieval music.

In conclusion, while we cannot definitively prove the widespread use of bass recorders before the 16th century, the evidence gathered from various sources strongly points to their existence. The topic warrants further investigation, especially in terms of exploring more iconographical, literary, and archaeological evidence to fill in the gaps of early recorder history.

An overview of the iconographical and literary sources

11th century: David and the Psalmists – Carved stone pillar in Bourbon-l’Archambault, Burgundy, depicting a pipe-like instrument with a thumb hole.

Early 14th century: Ormesby Psalter – Illumination in the Bodleian Library showing a cockerel-man playing a large pipe that could be a recorder, suggesting a possible bass.

14th century: Catedral El Salvabori – Spain, depicting an angel musician playing a large-sized flute.

14th century: St. German’s Church, Wiggenhall, Norfolk – Carving of an animal (likely a bear or monkey) playing a recorder, showing double finger holes and possibly a bent head (knick).

1370-72: La Prise d’Alexandrie by Guillaume Machaut – Mentions at least 20 kinds of flajols, indicating the existence of various pipe instruments.

1383: Archival records for flutes at the Court of Burgundy – Early evidence of recorder-like instruments in court ensembles.

1410: Inventory of Juan of Catalunya – Lists “tres flautes” (three flutes), possibly suggesting a recorder consort.

Early 15th century: Carved roof beam, King’s Lynn – Depiction of an angel playing a large recorder, possibly a tenor or larger size.

1426: Court of Burgundy – Order for a set of four recorders.

1443: Court of Burgundy – Another order for a set of four recorders.

1454: Court of Burgundy – Reference to four minstrels playing fleutres at a great banquet, implying a four-part ensemble.

1486-1506: Girona Cathedral – Depiction of two silver angels, one playing a tenor/basset recorder, the other playing a bass recorder with a bocal.

Bibliography

Bernstein, Lawrence F. 1982. “Notes on the Origin of the Parisian Chanson.” The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Jul. 1982), pp. 275-326.

Brand, B., & Rothenberg, D. 2016. Music and Culture in the Middle Ages and Beyond: Liturgy, Sources, Symbolism. Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Adrian, & Lasocki, David. 2006. “Renaissance Recorders and Their Makers.” American Recorder, January 2006.

Everist, M. 2011. The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Music. Cambridge University Press.

Everist, M., & Kelly, T. 2018. The Cambridge History of Medieval Music. Cambridge University Press.

Everist, M. 2004. French Motets in the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press.

Hascher-Burger, Ulrike (ed.), & Schaik, Martin van (ed.). 2016. “Filling the Gap: The Dordrecht Recorder (Before 1418) Revisited.” Klankbord: Newsletter for Ancient and Medieval Music. Accessed 01.05.2019. http://www.klankbordsite.nl/DownloadNieuwsbrief20Eng.pdf.

Hijmans, I. 2016. The Polyphonic Potential of Gruuthuse Melodies from a Central European Perspective: An Experimental Musicological Exploration. Accessed 01.05.2019. https://fillingthegapreconstructionproject.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/the-polyphonic-potential-of-gruuthuse-melodies-from-a-central-european-perspective-an-experimental-musicological-exploration.pdf.

Hijmans, Ita. 2015. Instrument Onbekend: De Reconstructie van een Blokfluitconsort uit het Midden van de Vijftiende Eeuw. Accessed 01.05.2019. https://fillingthegapreconstructionproject.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/instrument-onbekend-de-reconstructie-van-een-blokfluitconsort-uit-het-midden-van-de-vijftiende-eeuw.pdf.

Hijmans, Ita. 2014. Muziekgeheimen: Speuren naar Sporen van een Instrumentaal Ensemblerepertoire in het Vijftiende-Eeuwse Europa Benoorden de Alpen. Accessed 01.05.2019. https://fillingthegapreconstructionproject.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/muziekgeheimen-speuren-naar-sporen-van-een-instrumentaal-ensemble-repertoire-in-het-vijftiende-eeuwse-europa-benoorden-de-alpen.pdf.

Hunt, E. 1975. The Bass Recorder. Schott.

Griscom, W., & Lasocki, D. 2013. The Recorder: A Research and Information Guide. Routledge.

Lasocki, D. 2017. “Juan I and His Flahutes: What Really Happened in Medieval Aragón?” American Recorder, Winter 2017.

Lasocki, D. 2014. “De Bassetblokfluit [The Bass Recorder, 1660-1740].” Blokfluitist, 6(1): 4–7. http://www.instantharmony.net/Music/basset-recorder.longversion.pdf.

Lasocki, D. 2012. “What We Have Learned About the History of the Recorder in the Last 50 Years.” American Recorder, Winter 2012.

Lasocki, D. 2011. “Researching the Recorder in the Middle Ages.” American Recorder, January 2011.

Lasocki, D. 2003. “Musique de Joye: Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Renaissance Flute and Recorder Consort, Utrecht 2003.” STIMU.

Lasocki, D. “Basset and Bass Recorders, 1660–1740.” Accessed 01.05.2019. http://music.instantharmony.net/basset-recorder.longversion.pdf.

MacMillan, D. 2012. “The Bass Recorder – A Continuo Instrument?” Recorder Magazine, 32(4): 134–36.

Paalman, Deborah. 2009. Blockfluit. Accessed 01.05.2019. https://fillingthegapreconstructionproject.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/uit-de-collectie-van-archeologie-blokfluit.pdf.

Primus, Constance M. 1984. “The Bass Recorder in Consort.” The American Recorder, Vol. XXV, No. 3, August 1984.

Recorder Homepage. Anonymous Pre-14th Century Recorder Iconography. Accessed 01.05.2019. http://www.recorderhomepage.net/recorder-iconography/anonymous-pre-14th-century/.

Recorder Homepage. Anonymous 14th Century Recorder Iconography. Accessed 01.05.2019. http://www.recorderhomepage.net/recorder-iconography/anonymous-14th-century/.

Strohm, R. 2005. The Rise of European Music, 1380-1500. Cambridge University Press.

Thomson, J., & Rowland-Jones, A. 1995. The Cambridge Companion to the Recorder. Cambridge University Press.