Percussion Instruments of the Middle Ages

Trumpeters,

With brazen din blast you the city's ear;

Make mingle with rattling tabourines;

That heaven and earth may strike their sounds together,

Applauding our approach.

Antony and Cleopatra

Introduction

Here's the thing about medieval percussion: we don't have any. Not one drum survives from before 1600. No written music either, save for Thoinot Arbeau's Orchésography from 1589. Yet somehow, we know an astonishing amount about how these instruments were built, played, and woven into the fabric of medieval life.

One of the more depressing side of the research on early music is the scarcity of research on early percussion. The Cambridge Companion to Percussion starts its second part, The Development of Percussion Instruments, with 'Marimba revolution' and the 20th century. Good stuff. Not very medieval.

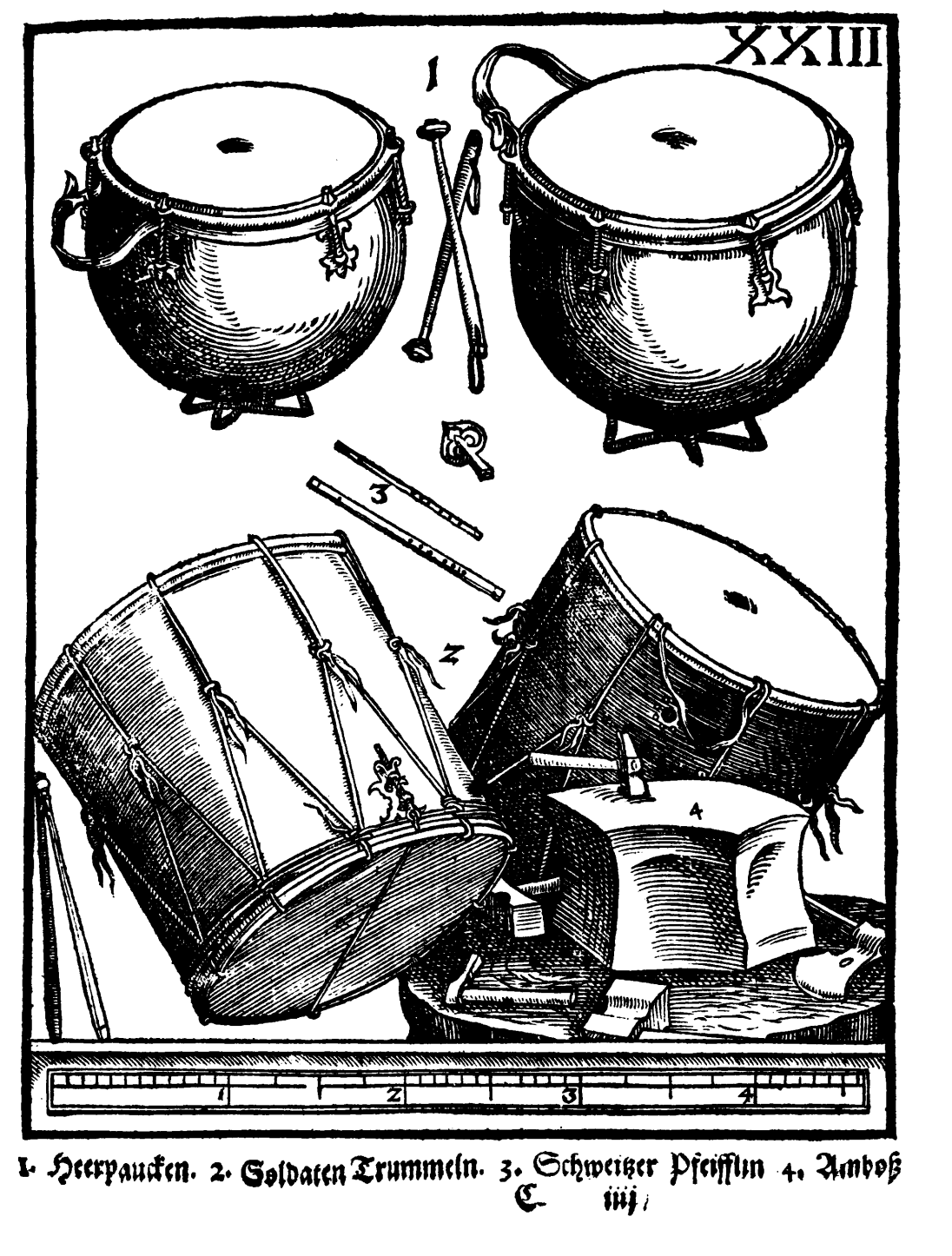

The clues come from not-so-unexpected places. Renaissance writers like Sebastian Virdung (1511) and Martin Agricola (1529) left us detailed treatises. Michael Praetorius and Marin Mersenne followed in the seventeenth century, creating a paper trail that reaches backwards into the medieval world. These texts don't just describe instruments; they reveal an evolution, a musical conversation between generations.

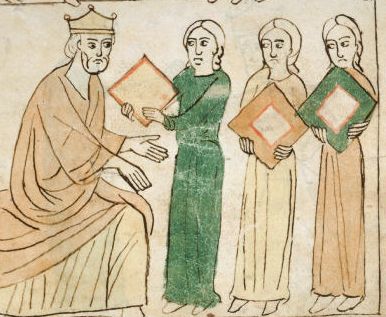

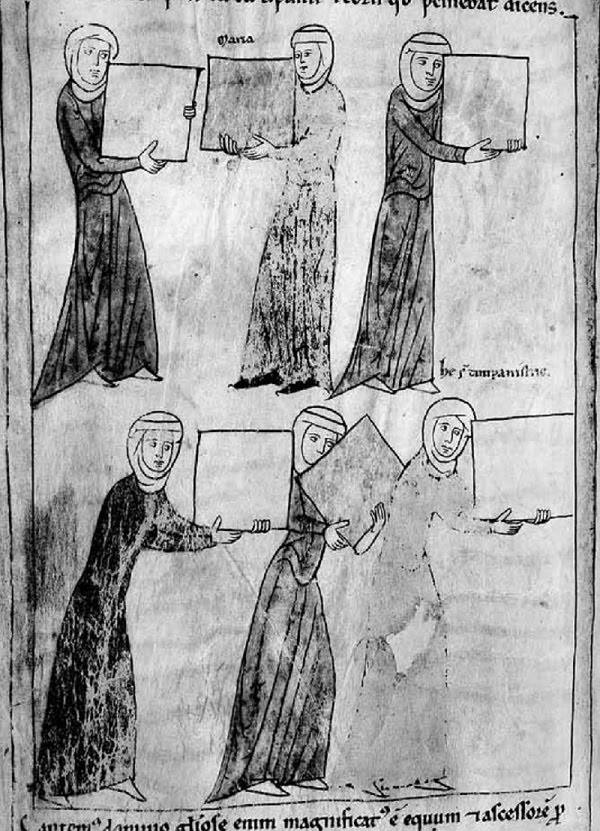

Then there's the iconography, and bloody hell, there's loads of it. Illuminated manuscripts, sculptures, stained glass windows: medieval artists were obsessed with depicting percussion. Frame drums, cylindrical drums, tabors, tambourines: they're everywhere. In dance scenes, processions, religious rites. These images tell us about scale, design, function. They show us a world where percussion wasn't background noise but central to the rhythm of life itself.

Some percussion instruments simply haven't changed much. Frame drums and tambourines today look remarkably similar to their medieval ancestors. The techniques used by a modern adufeira in Portugal or a tamburello player in Southern Italy? Likely not far off from what a medieval musician would have done. When you compare hand positions in a twelfth-century sculpture with those of a contemporary player, you're not imagining the past. You're seeing it.

The literature loves drums paired with pipes and trumpets: loud, martial, ceremonial stuff. But frame drums specifically? The texts go quiet. Despite appearing constantly in medieval art, their precise functions remain frustratingly vague.

Before the mid-twelfth century, the percussion palette was limited: circular frame drums dominated. Then came the New Instrumentarium: bells, the santur, square frame drums, clappers. The soundscape expanded, diversified, got louder.

A word about terminology, because this matters: in percussion, the same word can mean wildly different things depending on where you are, who's playing, what function the instrument serves. Even the word "drum" itself has a murky history. Old English didn't quite have 'drum' as we know it. You'd find 'timbre' or possibly 'druma', words connected to wood, sound, thunder. The Old Norse 'tromma', though? That's clearer. It survives in modern Scandinavian languages: Swedish 'trumma', Norwegian 'tromme'. A direct line from Viking halls to contemporary orchestras.

What we're left with is a paradox: no instruments, no scores, yet a vivid understanding of medieval percussion. Renaissance treatises pointing backwards, medieval art pointing everywhere, and modern traditions carrying forward techniques that refuse to die. Together, they paint a picture of a world where drums weren't just instruments but the heartbeat of social, ceremonial, and spiritual life.

Naker

The kettle drum, or timpani, occupies a distinguished position as one of the earliest percussion instruments incorporated into symphonic ensembles. By the 16th century, it had achieved prominence as a key component in both military and ceremonial contexts. Typically played in pairs, the kettle drum is often associated with trumpets, a pairing that underscores their shared roles in singling and processional functions. This connection is evident in Shakespeare's Hamlet (1600), where he observes:

The king doth wake tonight and takes his rouse,

Keeps wassail and the swaggering upspring reels,

And, as he drains his draughts of Rhenish down,

The kettle-drum and trumpet thus bray out

The triumph of his pledge.

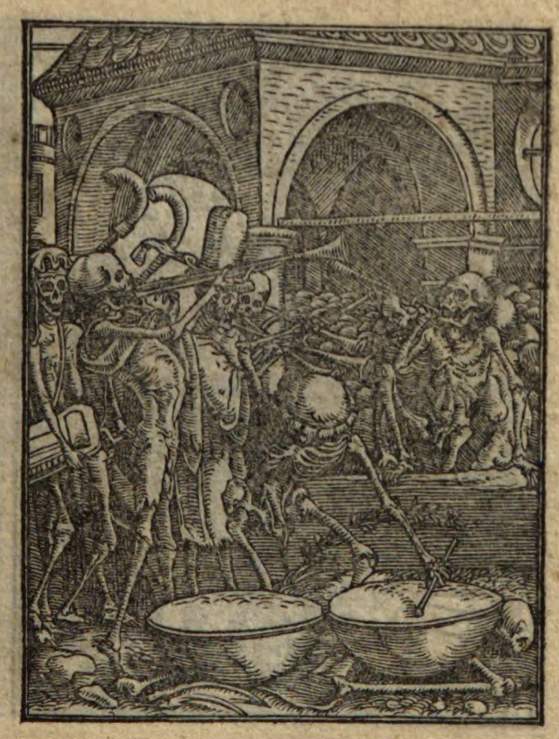

Visual representations of the kettle drum appear in significant artistic works of the period. Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543) included depictions of the instrument in his Dance of Death series (1523–1525, Bones of All Men), as well as the Dance of Death by Vincenzo Valgrisi (1490-1573, The Ossuary).

Similarly, Persian illustrations from the Shahnama (ca. 1525–30), such as 'Zal Slays Khazarvan,' portray drums mounted on horses and camels alongside trumpets.

Christian iconography also features the kettle drum prominently, as seen in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, attributed to Pieter Huys. Predecessors of the kettle drum, known as nakers, are depicted in 14th-century stained glass at Rouen Cathedral in Normandy. Additional representations of nakers appear in illuminated manuscripts, including:

Paris, BnF, NAL 3145, f. 53r.

Chambéry, BM, 004. f. 367v.

With snare. Chantilly, Musée Condé, ms. fr. 65, f. 26r.

With snare. 14th century misericord, Worcester Cathedral

A particularly unique portrayal of nakers is found in Paris, BnF, Français 184, f. 5. This 15th-century manuscript presents nakers in a serene setting, alongside a range of instruments, including strings, winds, a triangle, and a tambour à cordes.

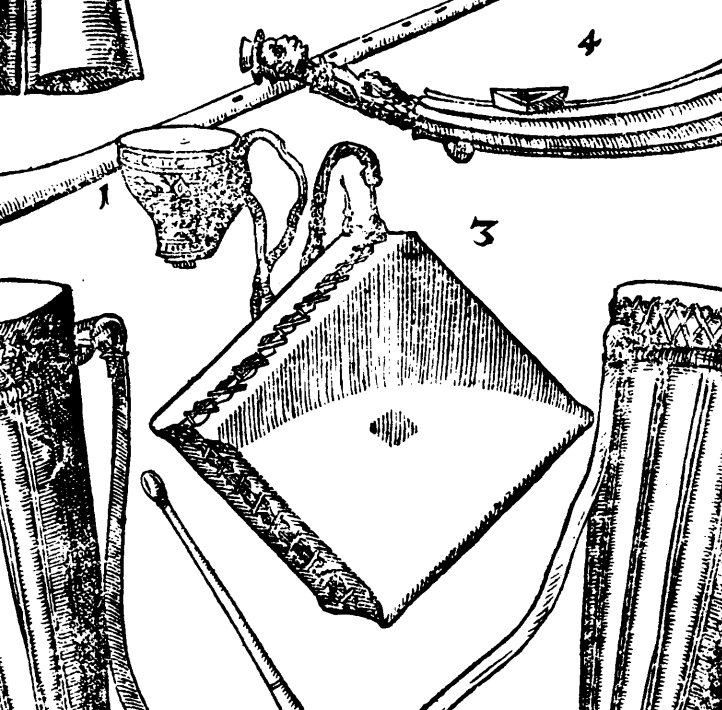

The kettle drum likely evolved from smaller portable drums such as the naker, itself a European adaptation of the Middle Eastern naqqāra, brought to Europe by returning crusaders. Typically, nakers were strapped to the performer’s waist or shoulders, or played on the ground, featuring bowls crafted from materials such as copper, wood, or earthenware, and drumheads fashioned from calf, goat, or donkey hides.

An intriguing transitional depiction is found in the 14th-century manuscript MS Bodl. 264, f. 113r. Here, nakers appear alongside a larger drum and a timbrel atop castle battlements, suggesting an evolutionary stage wherein the addition of snares and larger sizes bridged the gap between nakers and modern kettle drums.

Tambour

The tambour was everywhere and nowhere all at once. An elongated cylindrical drum, double-headed, with a single snare running across the batter head. Except when it wasn't. The truth is, there was no definite form. The most common version? Double-headed, cord-tensioned, played with a single stick. But medieval craftsmen weren't working from standardised blueprints. They built what worked, what sounded right, what could be heard over the din of a street festival or the chaos of a battlefield.

This was the drum of the people, the drum of soldiers, the drum that showed up in literature again and again alongside pipes and other instruments. Listen to how the poets heard it:

With esy pace and wele avysed, / Taberis and pypes yeden hem by / And alle maner of mynstrelsy

(Sir Orfeo, c. 1400)

They haueth in greet mangerie / Harpe, tabor, and pype for mynstralcie

(Ranulf Higden, Polychronicon, 1387)

And earlier still, Adam de la Halle in the late thirteenth century, cataloguing the full sonic chaos of medieval celebration:

Cil sert de harp, cil de rote / Cil de gigue, cil de viele / Cil de flaiiste, cil chalemele / Sonent timbre, sonent tabor

But here's where it gets specific, where we move from poetry to purchase orders. An entry in the Privy Purse expenses of Henry VII, dated 1492, records payment to '2 Sweches grete' for the sum of £2. Swiss drummers. Imported talent. This wasn't unusual. The association of drum and fife, that piercing martial combination, is documented in the Chronicles of the City of Basel as early as 1332. The Swiss had a reputation. Their mercenary companies were famous not just for their pikes but for their sound: the relentless beat of drums and the shriek of fifes that preceded them into battle.

England wanted that sound. So they paid for it. Two Swiss professionals, brought across the Channel to teach, to perform, to bring that distinctive Basel rhythm to the English court.

The tambour wasn't refined. It was functional, adaptable, loud. It kept time for marching feet and dancing bodies. It announced arrivals and marked departures. And unlike the delicate instruments of the chamber, it survived in the streets, in the squares, in the memories of poets who heard it and couldn't help but write it down.

No surviving tambours from the period. But we know they were there. We can almost hear them still.

Frame Drums

Start with a word: al-duff. As early as the 6th century, this Arabic term meant frame drum, full stop. Didn't matter if it was big or small, round or square, had jingles or didn't, covered on one side or both. Al-duff covered the lot. It's the alpha and omega of frame drums across the Mediterranean, the linguistic thread connecting peoples, music, and culture from the Sahara to Iberia.

The variations tell the story of movement. Daff, deff, doff, duff: these are the tambourines of nomadic tribes crossing the Sahara, each slightly different, each adapted to the needs of the players. Some have jingles, some don't. Size varies. The bendhir takes it further, featuring gut strings pressed against the drumhead that vibrate when struck. It's a snare effect, essentially the same mechanism you'd find in a modern drum kit, but handmade and ancient.

The names alone are a map: bendhir, bandir, pandair, pandero, meze, timpanum. Each one a clue to the origins of the tambourine and the adufe. The term 'pan' likely comes from Sumerian, meaning 'skin', which makes perfect sense when you consider what these instruments are made from. Go back further still: Sumerian terms like alal, balag, and adapa date from 4000 to 5000 BCE and connect to this same family of instruments. Meze and mizhar have been around for roughly 4000 years, appearing in ancient texts describing tambourines used in ceremonial and ritual contexts. That use continues today in Egypt. Same instrument, same purpose, millennia later.

The linguistic web spreads wider: dayareh, dayira, daire, dareh, dahare, tur (Polish), atari (Swahili), tar (Persian). Each term marks a place where the frame drum took root, adapted, became essential.

In the 8th century, Persian musicians flooded into the Iberian Peninsula via the Abbasids and Umayyads, setting up shop in Córdoba and Seville. Many of the instrument names and musical terms still used in North Africa today? Persian, not Arabic. That cultural exchange shaped everything, including the evolution of the adufe.

By the 13th century, the adufe was firmly planted in Iberian culture. Martín de Ginzo, a minstrel in the court of Alfonso X, references it in the Cantiga de Amigo.

The adufe as we know it today in the Iberian Peninsula has clear cousins across the strait in North Africa: the deff, the doff. In Arabic, you add the definite article 'al' to 'duf' and you get al-duff, the frame drum, the particular one within Arabic musical tradition.

What's remarkable isn't just the longevity but the consistency. Frame drums haven't fundamentally changed in thousands of years because they don't need to. The design works. Skin stretched over a frame, struck with hands, sometimes embellished with jingles or snares. Simple, portable, versatile. Perfect for ritual, perfect for dance, perfect for wandering musicians crossing deserts and mountain ranges.

Al-duff. One word, one instrument, countless variations. From ancient Sumer to medieval Córdoba to modern Cairo. Still here. Still playing.

Square frame drums don't make sense until you see one. Then it's obvious: the shape is practical, it's distinctive, and it produces a sound completely different from its round cousins. Less defined pitch, quicker decay. The attack is sharper, the resonance shorter. Perfect for rhythmic drive, for cutting through other instruments, for keeping a crowd moving.

The history stretches back further than you'd think. The tomb of Rekhmire in Egypt, dated to 1500 BCE, shows square frame drums in use. North Africa, then. That's the starting point. Fast forward to the 8th century and the Moorish invasion brings these instruments, along with countless other cultural treasures, to the Iberian Peninsula. The Moors came from Mauretania in northwest Africa, and they brought their music with them.

Portugal gains independence in 1143, shakes off Arab rule, establishes itself as a kingdom. The square frame drum stays. The iconographic evidence is overwhelming: this instrument was far more widespread and culturally significant during the medieval period than it is now. The early 12th-century Tavira Vase gives us one of the earliest surviving representations in Iberia.

By the mid-13th century, European iconography is full of them. You see square frame drums at Barruelo de los Carabeos, Igreja de Santa Maria de Yermos, in the Maciejowski Bible (Paris, MS M.638, fol. 39r), in four windows in Troyes, Grand Est, France. These are the earliest European depictions we have.

Around 1300, manuscript W.102 (78v) shows something crucial: the square frame drum being played with a beater. Whether jingles, bells, or snares were placed inside remains uncertain, but we know the sonic possibilities expanded over time. The double-headed construction, with two skins closing the structure, doesn't appear clearly depicted until the 13th century in the Pierpont Morgan Library Old Testament. By 1619, Michael Praetorius's Syntagma Musicum shows the stitching that joins the two skins in explicit detail.

Construction was local and practical: pine for the wooden frame, goat, sheep, or lamb skins for the drumheads. Materials at hand, craftsmanship passed down through generations.

In Portugal, the adufe sometimes features bordões, snares placed inside the instrument that add a buzzing, rattling texture to the sound. It's the same principle as the bendhir's gut strings: turning a simple frame drum into something more complex, more textured.

The adufe today is most famous in Portugal's Beira Baixa region, particularly in religious festivals. But here's what makes it genuinely distinctive: it's a woman's instrument. Women build them, decorate them, play them. This association isn't incidental or modern. The Biblia de Pamplona from 1197 already depicts this connection between women and the square frame drum in festivals and community celebrations.

Similar instruments appear across the region with different names: the pandeiro mirandês in Northeast Portugal, the pandeiro quadrado in Spain and Galicia. The term "pandeiro" (masculine in Spanish/Galician) derives from the Persian-Arabic bendayer (or ben-dair), another frame drum variant.

In Peñaparda, Salamanca, the square frame drum sits at the heart of traditional music and local festivities. The playing technique there is remarkable: the instrument is held perpendicular to the body, supported on the knee, struck with a mace or club in the right hand. Meanwhile, the left hand, using the big toe to hold a band, strikes the drum with the palm in a distinctive rhythmic pattern called backsets. This same technique appears in Morocco. Connection through practice, technique travelling across the strait.

Traditionally, women used the square frame drum to accompany singing. More recently, thanks to musicians like Eliseo Parra, the instrument has found a place in folk music ensembles across Spain. In some regions (Astorga, León, Asturias, Ourense in Galicia), it remains strongly associated with women, though men play it too, especially alongside bagpipes, drums, tambourines, and shells.

The instrument even made it to Brazil, appearing in Folias do Espírito Santo, Pastorais, and Ranchos dos Reis, particularly in São Paulo. Brazilian scholars suggest African origins, brought over by the Portuguese. The routes of colonialism and slavery carried these instruments across the Atlantic, where they took root in new contexts.

After the 15th century, depictions of square frame drums become rare. The instrument seems to fade from the iconographic record. Then Praetorius brings it back in 1619, calling it "Mostowitesihe Trumreln oder Paucken." A German Renaissance composer documenting what was, by then, becoming a relic of an earlier age.

But relics have a way of surviving. The adufe still sounds in Portuguese villages. The pandeiro quadrado still marks the rhythm in Spanish festivals. Square frame drums never disappeared. They just went underground, kept alive by communities that remembered what they were for: celebration, ritual, the music that marks time and brings people together.

From an Egyptian tomb to a Portuguese chapel. Four thousand years, give or take.

References

Primary Sources

Agricola, Martin. Musica instrumentalis deudsch. Wittenberg, 1529.

Arbeau, Thoinot. Orchésography. Langres, 1589.

Mersenne, Marin. Harmonie universelle. Paris, 1636.

Praetorius, Michael. Syntagma Musicum. Wolfenbüttel, 1619. Translated by David Crookes.

Virdung, Sebastian. Musica getutscht. Basel, 1511.

Secondary Sources

Blades, James. Percussion Instruments and Their History. London: Faber and Faber, 1970.

Blades, James, and Jeremy Montagu. "Early Percussion Instruments from the Middle Ages to the Baroque". Early Music, vol. 4, no. 1, Jan. 1976, pp. 19-31.

Braun, Joachim. "Musical Instruments in Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts". Early Music, vol. 8, no. 3, Jul. 1980, pp. 312-327.

Cohen, Judith. "This Drum I Play: Women and Square Frame Drums in Portugal and Spain". Ethnomusicology Forum, vol. 17, no. 1, 2008, pp. 95-124.

Dias, Ana Carina. "O adufe: o contexto histórico e musicológico". M.A. thesis, Instituto Politécnico de Castelo Branco, 2011. https://comum.rcaap.pt/handle/10400.26/356

García de la Cuesta, Dani. "Sobre los Panderos Cuadrados". 2006. https://adufes.com/website/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Sobre_los_panderos_cuadraos.pdf

Maia, Maria Garcia Pereira. "Vaso de Tavira". Museu Municipal de Tavira/Câmara Municipal de Tavira, 2014. https://issuu.com/museum_tavira/docs/vaso_de_tavira/1

Molina, Mauricio. Frame Drums in the Medieval Iberian Peninsula. Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf, 2010.

Montagu, Jeremy. The World of Medieval and Renaissance Musical Instruments. London: David & Charles, 1976.

Montagu, Jeremy. Making Early Percussion Instruments. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Montagu, Jeremy. "On the Reconstruction of Mediaeval Instruments of Percussion". The Galpin Society Journal, vol. 23, Aug. 1970, pp. 104-114.

Montagu, Jeremy. "The Tabor, Its Origin and Use". The Galpin Society Journal, vol. 63, May 2010, pp. 209-216.

Pereira, Tiago. A Música A Gostar Dela Própria: 128 Vídeos Sobre o Adufe na Actualidade. https://amusicaportuguesaagostardelapropria.org/videos/?_sft_instrumentos=adufe

Silva, Rui Pedro de Loureiro. "Al-duff: Bases para a Aplicação das Técnicas de Frame Drums Mediterrânicos ao Adufe, Séc. XXI Adentro." M.A. thesis, ESMUC/Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2012. https://adufes.com/website/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Adufe-Tese-MasterDezembro-2016.pdf

Silva, Rui. "Adufe para o séc. XXI: sem braseiro, sem secador de cabelo, sem cobertor eléctrico". In Iconografia Musical: Organologia, Construtores e Prática Musical em Diálogo, pp. 142-157. Lisbon: CESEM, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2017. https://adufes.com/website/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/NIM_28FEV2018.pdf

Torres, Cláudio. "The Tavira Vase". Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers, 2025. https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;pt;Mus01_C;9;en