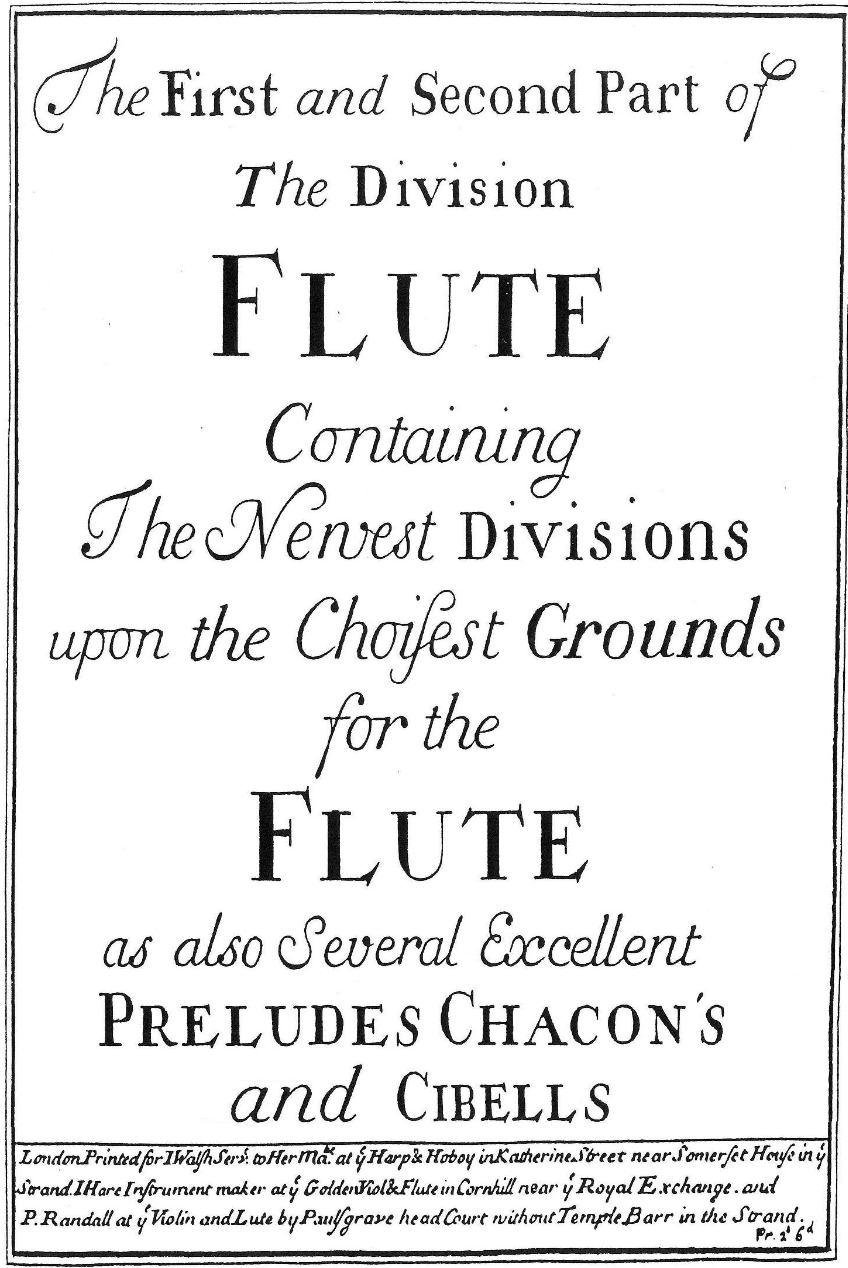

The Division Flute

The story goes something like this...

After what felt like an aeon of Puritan gloom, when public music making could land you in serious trouble, Charles II came swanning back from France in 1660 with an head full of Lully and a taste for continental fripperies.

Overnight quiet was rebranded as frightfully un-English, and every gentleman and gentlewoman of quality grabbed whatever noisemaking implement came to hand and set about blowing flutes, bashing organs, and sawing at viols with such lusty vigour, furniture trembled in fear. Anything capable of emitting a vaguely Frenchish squeak was dragooned . If it could conceivably accompany a minuet at Versailles, it was declared absolutely de rigueur.

This craving for all things continental created a fertile commercial climate, one that, by 1706, yielded The Division Flute .

As ever, the reality turns out to be more complicated.

The Oxford Confession (1654)

In 1654, John Webster, a former Parliamentary army chaplain turned vicar, published Academiarum Examen , having a proper go at Oxford's curriculum. The university, he huffed, was teaching only 'that vulgar and practical part' of music 'which serves as a spur to sensuality and voluptuousness, and seems to be the Companion of Melancholicks, Fantasticks, Courtiers, Ladies, Taverns, and Tap-houses.'

Seth Ward, Savilian Professor of Astronomy, stepped up with his Vindiciae Academiarum . He defended the teaching of music theory, but admitted 'the Theory of Musick is not neglected, indeed the Musick meeting, by the Statutes of this University, appointed to be once a weeke, hath not of late been observed, our Instruments having been lately out of tune, and our harpes hanged up...'

Ward also noted that Webster's complaint about tavern music was correct. 'The informal and relatively ribald music of the students undertaken for merriment and amusement continued unabated.'

Oxford's formal, academic music meetings had ceased, while informal music-making in taverns continued apace. Ever thus.

The Puritan Interregnum and the Birth of a Market

When you ban public music-making by the doom of law, it goes underground.

During the Commonwealth, musicians and composers sensibly scarpered to the hospitable bosoms of aristocratic households, and played in private chapels where the gooniī Cromwelliani couldn't reach them. But , as is the way of human affairs, repression has a knack for metamorphosing into opportunity.

Out of this stifling murk arose a market for amateur music. People wanted to play at home. They wanted instruction books, collections of tunes, methods that could turn a moderately talented bloke or lady into a passable performer.

John Playford saw the opportunity and ran with it. The son of a Norwich family, Playford was apprenticed on March the 23rd, 1639/40 to John Benson, a stationer in St. Dunstan's Churchyard, and took up his Freedom on April the 5th, 1647.¹ During his apprenticeship, Benson employed Thomas Harper as a printer, the same Harper who used the printing materials and music-types that had formerly belonged to Thomas Este, and 'for close on a hundred years, until the presses and types passed to the Crown in 1686, a great deal of all the music published in England was printed with those same types.'² Playford was rubbing shoulders with the same tools that had churned out England's top-notch Elizabethan tunes.

Playford snagged himself the gig as clerk to The Temple Church and set up shop right by the door. Throughout 'the whole forty years of his trading,' Playford 'won the trust and friendship—or more truly the affection—of the musicians who contributed to his publications and of the amateurs who bought them.'³ By the time the Restoration arrived the infrastructure was furnish'd complete .

Evidence of this emerging market appears in unexpected places. Playford's wife Hannah ran a boarding school for 'young gentlewomen' in Islington during the late 1650s where students were 'instructed in all manner of curious work, as also reading, writing, musick, dancing, and the French tongue.' Clear evidence musical instruction persisted even during Puritan rule. ⁴ That such schools operated openly during the Commonwealth suggests the authorities' grip on private music-making was never absolute.

Playford's business acumen extended beyond mere publishing. Like many music sellers of his era, he recognised that survival required diversification. His fellows in the calling did the same: John Clarke at the 'Golden Viol' in St. Paul's Church Yard published instruction books whiles Pops ran the shop, and Richard Meares the elder combined music selling with dealing in 'the best sorts of cutlery wares at reasonable prices.'⁵ This pattern of combining music with other trades reflected the precarious economics of the Commonwealth period when public musical activity remained curtailed.

Playford's attention to provincial customers was not mere marketing puffery. His books were cruising way past London streets, hitting spots like Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, and Northamptonshire.⁶ Take the Henry Atkinson manuscript, compiled in Northumberland in 1694/5, for example: tunes cribbed straight from Playford show that his printed repertoire had penetrated even the remotest corners.⁷ Distribution networks included regional booksellers (William London in Newcastle-upon-Tyne stocked ten Playford titles in his 1657 catalogue⁸) as well as music teachers, London-based agents, and family networks all funnelling metropolitan music into the hands of eager provincial amateurs.

What the Restoration changed was the aesthetics. The court returned, and with it came wave after wave of continental musicians.

The Violin Invades England

Before Charles II got back from France, the violin was about as English as spaghetti, played mostly by imported musicians and confined to courts, while the locals twiddled their viols and muttered 'thanks, but no thanks'.

(see The Viola d'amore ).

His Majesty had spent his exile soaking up Gallic musical culture, and when he reclaimed the throne, he brought the Frenchified fiddle frenzy with him.

The Italian show-off Nicola Matteis rolled up and promptly caused absolute pandemonium with his nimble fingers and fancy bowing. Giovanni Battista Draghi settled in the capital in the 1660s and never left, working in the court and theatre. The Albrici brothers joined the fray, singing in an exclusive Italian folla at court from 1663. And from these musicians the English encountered something they'd never heard before: the violin as a solo instrument capable of astonishing technical display.

The infrastructure supporting this continental influx was centred around St. Paul's Cathedral, which became the rallying point for London's professional and amateur musicians. The cathedral's musical services attracted audiences, whiles the surrounding taverns and coffee houses fostered musical mardle and commerce.⁹ Music shops clustered in the Church Yard: John Clarke at the 'Golden Viol,' John Young at the 'Dolphin and Crown,' and later Richard Meares, who moved from Leadenhall Street to establish himself at the 'Golden Viol and Hautboy' on the north side.¹⁰ This geographical concentration created an ecosystem where continental and English musical practices collided and merged, with Italian violin techniques demonstrated in tavern concerts above Young's shop and French recorder music sold in print from just doors away.

What's in The Division Flute, Actually?

The transverse flute was practically unknown in England at this point. The recorder, introduced from France in the 1670s, was all the rage among amateur dabblers who fancied themselves connoisseurs. Walsh's collection features nineteen divisions on a ground, showcasing various approaches to melodic elaboration.

Samuel Pepys recorded buying a copy of The Musical Companion on April the 15th, 1667, noting he 'found a great many new fooleries in it,' and three days later he 'tried two or three grave parts in Playford's new book.'¹¹

The commercial success of such publications attracted competitors. By the 1690s, Playford's near-monopoly faced challenges from newcomers, like John Walsh, who entered the trade in 1692 as 'musical instrument maker in ordinary to the King.'¹² Walsh quickly grasped the market Playford had cultivated, issuing The Self Instructor for the Violin in 1695 and The Compleat Flute Master the same year, with a second edition following in February 1696.¹³ These tutors, sold at eighteen-pence, were 'fairly engraven on copper plates', a technological advancement that would soon transform music publishing by allowing the unification of note tails and quavers (or eighth-notes if you're that way inclined), which moveable type could not achieve.¹⁴

Despite Playford's marketing claims of enabling self-instruction 'without the Assistance of any Teachers,' his prefatory material consistently acknowledges the need for professional guidance.¹⁵ In Musick's Hand-maid (1678), he suggests 'a little assistance from an able Master' would help students decipher the lessons, and Thomas Greeting's Pleasant Companion similarly directs beginners to seek 'a little assistance of a skilful Master.'¹⁶

By the time John Walsh swung open the doors of 'The Harp and Hoboy' on Catherine Street circa 1695, Playford’s musical empire was already running like a well-oiled spinet.

Walsh had learned the lesson of Playford's success, but he operated on a different scale entirely. Where Playford peddled English ditties and domestic instruction manuals, Walsh cast his net across the continent. Corelli in Amsterdam (published by Estienne Roger)? No problem. His partnership with John Hare, kicking off before 1700, turned Walsh into a publishing powerhouse the likes of which early eighteenth-century London hadn’t seen.

These printed collections functioned as teaching aids and standardised repertoire saving teachers from writing out examples repeatedly, while providing students with materials to practice between lessons.¹⁷

Playford's publication of John Hilton's Catch that Catch Can found particular success in London's tavern culture. Roger North described a tavern near St Paul's where amateur musicians gathered weekly, noting 'their musick was chiefly out of Playford's Catch Book.' Print enabled recreational music-making beyond elite circles and formal music meetings.¹⁸ This 'Mutuall Society of Friends in a Modest Recreation' (the phrase Playford used to describe his target audience) represented the urban 'middling sort': shopkeepers, foremen, and professional men for whom regular payments to private teachers 'were close to the limit of what seemed affordable.'¹⁹

The first part of The Division Flute adapts pieces from The Division Violin with modifications to accommodate the recorder's range and capabilities. Different keys, reordered divisions, that sort of thing. The grounds themselves often derived from folk tunes, popular songs, or dance music. Everyone knew these tunes. That was rather the point. You'd recognise the foundation and be impressed by the inventiveness of what the performer built on top of it.

It's rare to find these tunes in print before 1651. Not more than a score of them appear in earlier publications. The tunes appear primarily in manuscripts: 'the Fitzwilliam and Lady Nevell's Virginal Books, occasionally in Cosyn's Virginal Book, Ballet's, Dallis', Elizabeth Rogers' and Jane Pickering's Lute Books, and a few in the lute-collections at Cambridge.'²⁰ This manuscript circulation is precisely what makes the tradition so fluid and collaborative.

The Manuscript Underground

Across a whole network of manuscript sources, bass viol players, violinists, and recorder players appear to be working with the same material, adapting it to their instruments, swapping techniques, and nicking each other's best bits.

When Playford published The Division Violin in 1684, shortly before his death, he was drawing on material which had been circulating in manuscripts among bass viol players. You can trace specific pieces back through various sources, each with different attributions, different strain orders, different embellishments. Take the divisions on Powlwheels Ground . Depending on which manuscript you consult, they're attributed to Powlwheel himself, Henry Butler, Peter Young, or Christopher Simpson.²¹ The uncertainty is such that even modern scholars remain 'uncertain of the true attribution,' though the various manuscript inscriptions ( Powlwheel , P.W.'s own follow , and attributions to Pol (e) wheele) suggest Powlwheel himself may have written divisions on his own ground.²²

The bass viol players had their versions. The violinists adapted them. The recorder players got hold of them...

This how music worked. You heard something good, you adapted it to your instrument, maybe you improved it, and the next person did the same. A manuscript at the Newberry Library contains bass viol versions of pieces from The Division Violin , with alterations suggesting the copyist was working from a later edition.

The fluidity of ownership paralleled the fluidity of the texts themselves. Surviving copies show multiple owners over decades. One copy of Musick's Delight on the Cithren (1666) bears the signature 'Jarvis Houghman 1715,' while Durham University Library's Pleasant Companion (1676) contains three different owners' names.²³

Blank staves left by printers were regularly filled with additional ornaments, transposed parts, or entirely new pieces, turning printed books into personalised commonplace books which continued to grow throughout their working lives.²⁴

The physical appearance of these books also tells us something about their nature. About a third of the tunes in The Dancing Master are printed in the 'Old French violin clef' and an assortment of small, archaic music type is used. This archaic type may signify 'older' tunes, though this notion has no firm foundation. The varied notation more likely reflects Playford's need to 'scrape together a sufficiency of small music type' from the available resources of Este's materials.²⁵

The typography itself is evidence of material continuity with Elizabethan music printing.

This collaborative manuscript culture existed alongside an increasingly sophisticated print technology. The shift from moveable type to engraved copper plates revolutionised music printing in the 1680s and 1690s. Thomas Moore's invention of 'the new tied note' around 1688 finally allowed quavers and semiquavers to be united as in modern notation, while J. Heptinstall and William Pearson advanced musical typography further.²⁶ By 1699, Pearson was advertising his 'new London Character' in publications like Twelve New Songs with a Thorough Bass , boasting that the music was 'fairly engraven on copper.'²⁷ This insistence on engraved notation in advertisements reflects the difficulty modern players find in reading from crude seventeenth-century musical typography. The advantage of an engraved score was its clarity and the ability to unite note values impossible with moveable type.²⁸

Meanwhile, here's a Late Victorian argument about Puritan organ policy...

The Great Victorian Organ Debate (1899-1900)

In Notes and Queries during 1899-1900, Victorian scholars debated whether the Puritans actually destroyed organs or merely relocated them.

Key participants:

H. Davey : Argued organs were destroyed and Cromwell bore responsibility W.C.B. : Attempted to exonerate Cromwell personally Mr. Cummings : Disputed technical details about organ music and manuscripts

The Case of the Magdalen College Organ

Davey documented the Magdalen College organ's movements:

Pulled down from Magdalen College during the Commonwealth Set up at Hampton Court Palace 'by Cromwell's command' (where, apparently, it was played by John Milton) Pulled down from Hampton Court after the Restoration Set up at Magdalen College again Pulled down in 1737 Installed at Tewkesbury Abbey Still existing in 1900 (and still existing today, although various people have added bits in the meantime).

Davey's point: 'As a practical organist, he knows (perhaps W.C.B. does not know) that an organ is not "destroyed" by being "pulled down."'

W.C.B. argued 'Qui facit per alium facit per se' (what one does through another, one does oneself) claiming that without explicit evidence Cromwell personally ordered destruction, he couldn't be blamed. But Cromwell explicitly ordered the Magdalen organ installed at Hampton Court for his own use.

Organs in Taverns

Davey mentioned 'the recorded preservation of the organ of Rochester Cathedral in a Greenwich tavern' and referenced the Harleian Miscellany (Volume X, page 191) 'concerning organs in taverns.'

At least some organs were preserved in taverns rather than destroyed, though the extent of this practice is unclear from the available evidence.

The Genealogy of Division Playing

You can trace this tradition back through the sixteenth century. Diego Ortiz's Trattado de Glosas (1553) spelled out how to dress up your viol lines . Sylvestro Ganassi's Opera Intitulata Fontegara (1535) did the same for recorders. Italian theorists and composers including Dalla Casa, Bassano, Rognoni, Bovicelli, and Virgiliano all contributed to this body of knowledge. Their collective message: take a simple tune, jazz it up.

Christopher Simpson's The Division Viol (1659), subtitled The Art of Playing Ex Tempore upon a Ground , serves as the crucial English link in this chain. It's both an instructional treatise and a bridge between the long Italian tradition and the later English works like The Division Violin and The Division Flute . Simpson explained the principles clearly: here's your ground, here's how you think about dividing it, here are examples of increasing complexity, now go your ways and do it yourself.

Reading's Ground

Reading's Ground is a chaconne which appears in several sources, traditionally attributed to the keyboardist John Reading, though Valentine Reading is now considered more likely. It first shows up for recorder in Humphrey Salter's The Genteel Companion (1683), and the versions in both The Division Violin and The Division Flute are simplified from the original.

In The Division Violin , this is the only piece requiring scordatura tuning, one of the earliest English examples of printed violin scordatura (more on this can be found in The Viola d'Amore ).

Though here's the thing: the scordatura isn't necessary in Reading's Ground. You can play the entire piece, including the double stops, on a conventionally tuned violin. Why retune? Either it's an association with the Austrian and Bohemian schools of playing, where scordatura was more common, or possibly it's borrowed from folk music practice. The retuning would emphasise sonority over virtuosity, which fits with the aesthetic values of the period.

Salter's Graces

Salter's Genteel Companion gives us invaluable details about ornamentation. He explains the graces recorder players were expected to master. The Beat , executed by shaking the finger on the designated hole and releasing it. The Shake , similar but explicitly marked in the notation. The Slur or Slide , connecting two or three notes with a single breath. The Slur and Beat, a more complex combination. The Double Shake , played by shaking the fourth finger of the left hand while maintaining the other fingers in position.

Cross-Pollination & Shared Repertoire

Several pieces appear in both The Division Violin and The Division Flute : Johney Cock Thy Beavor (also called Newmarket), Greensleeves, Tollet's Ground. The differences are mostly practical adaptations. Different keys to suit the instrument's range. Octave jumps moved around. Old Simon the King varies more significantly, with notable differences in the bass line.

Old Simon the King has a whole editorial history of its own. The first edition of The Division Violin had errors. The 1685 'Second Edition, much enlarged' made corrections, replacing the eleventh strain with 'The Second Part' and removing a problematic B-flat from the key signature. If you want to perform this piece now, you should follow the later editions and the keyboard version from The Second Part of Musick's Hand-maid (1689), which omit the B-flat.

These variations show how fluid naming conventions and musical transmission were in seventeenth-century England. No single authoritative version existed; instead, multiple versions circulated, each shaped by the needs and capabilities of different instruments and performers.

Newmarket/Johney Cock thy Beavor a ppears in Wit and Mirth or Pills to Purge Melancholy, with the text:

To Horse, brave boys of Newmarket , to Horse, You'll lose the Match by longer delaying; The Gelding just now was led over the Course, I think the Devil's in you for staying: Run, and endeavour all to bubble the Sporters, Bets may recover all lost at the Groom-Porters; Follow, follow, follow, follow, come down to the Ditch, Take the odds and then you'll be rich.

For I'll have the brown Bay, if the blew bonnet ride, And hold a thousand Pounds of his side, Sir; Dragon would scow'r it, but Dragon grows old; He cannot endure it, he cannot, he wonnot now run it, As lately he could: Age, age, does hinder the Speed, Sir.

Now, now, now they come on, and see, See the Horse lead the way still; Three lengths before at the turning the Lands, Five hundred Pounds upon the brown Bay still: Pox on the Devil, I fear we have lost, For the Dog, the Blue Bonnet , has run it, A Plague light upon it, The wrong side the Post; Odszounds, was ever such Fortune.

The Cebell

The Cebell, lurking in the pages of The Division Flute (1706), is an example a Baroque number with pastoral dance pedigree. The term 'Cebell' likely derives from the French cibell , though its ultimate origin is more specific and intriguing than the name alone suggests.

Musicologist Thurston Dart traced the cibell's ancestry to Jean-Baptiste Lully's opera Atys (1676), and the chorus 'Nous devons nous animer d'une ardeur nouvelle' that accompanies Cybele's descent at the end of Act I. This connection explains the name: various manuscript sources refer to the tune as 'Descente de Cybelle,' which the English, with their usual fondness for mishearing and misprinting, evolved into 'Cibell,' 'Cebell,' and 'Sybel'.

In The Division Flute , the Cebell is attributed to 'Signor Baptist' and presented as a basis for unaccompanied divisions. The Division Violin includes 'Queen Ann's Sebell' and another Sebell positioned after 'Reading's Ground,' while various sources reference 'The King's Sebell,' 'The Old Sebell,' and 'Purcell's Sebell.' This proliferation of titled variants suggests that the cibell had become not just a single tune but a recognised musical form with royal associations and attributions to specific composers.

What makes the English cibell particularly fascinating is that it represents a double transformation. Henry Purcell gave it a makeover 'in imitation' of Lully's original. His version became so influential that it earned its own moniker: 'Purcell's Sebell.' Subsequent English cibells (by composers such as Jeremy Clarke, William Croft, Godfrey Finger, and others) were then modelled on Purcell's version rather than directly on Lully's original, making the form what Dart describes as 'a parody of a parody.'

We find examples too in Wit and Mirth , with 'A Dialogue in the Kingdom of the Birds, to the famous Cebell of Signior Baptist Lully.'

Continuo Practice in Mid-seventeenth Century England

The basso continuo arrived in England fashionably late and was received with the usual mixture of curiosity and suspicion. While it had been holding the groove down across Europe for years, England took its time, adopting the practice cautiously and on its own terms.

The Theorbo

From the 1630s through the early eighteenth century, the theorbo-lute reigned supreme as the preferred continuo instrument for English vocal music. This preference is documented in multiple contemporary sources: Playford's publications from 1653 onward consistently designated songs 'to be sung to the theorbo-lute or bass viol.' and that, apparently, was that.²⁹ While the continent flirted with keyboards, England stuck loyally to its long-necked friend. As late as 1676, Thomas Mace wrote that the theorbo was 'still made use of, in the best performances of music (namely, vocal music).'³⁰ The music itself gives the game away. Crack open them Caroline song collections and boom, the overwhelming fondness for G major and its immediate neighbours reflects the theorbo's standard tuning, calling the shots from the low end.³¹

The theorbo’s claim to continuo fame was built in. With six courses and a set of outrageously long diapason strings dangling off its extended neck. The bass strings sounded 'so strong and so long' that the line practically walked itself, leaving the bass viol twiddling its thumbs like ' Uh… you got this, bro?' while the theorbo did all the heavy lifting.³²

It wasn't until the end of the seventeenth century that the harpsichord got its act together in England.³³ The organ had been holding court in sacred music and lending a hand to polyphonic crews since the 1630s, but when it came to solo vocal jams, the theorbo-lute still ran the show,³⁴ continuing the native lute ayre tradition dating back to the Elizabethan period.³⁵ Besides, harpsichords were lumbering, wallet-busting beasts , while theorbos were portable and relatively affordable.³⁶

A Distinctively English Sound

Theorbo playing, as Mace immortalised in Musick’s Monument , was anything but sleepy. Realisations were alive with personality: scuttling runs, delicate chord patterns... a whole arsenal of guitar-style tricks: broken chords, strums, and flourishes. The theorbo’s extended diapason register invited all sorts of octave gymnastics.³⁷ This flashy, ornament-heavy approach was a world away from the strict, polyphonic accompaniments of Elizabethan lute ayres .³⁸ The theorbo’s mellow, intimate voice left a lasting fingerprint on English vocal music. Its relatively soft volume nudged composers and performers toward chamber-style settings, where voice and accompaniment could weave tightly together. That close-knit, conversational interplay became a defining feature of English song which stayed front and centre well into the Restoration era.

The Transcription

I've made some deliberate choices which deviate from eighteenth-century English practice. I've included a basso continuo line throughout the divisions instead of providing a single line at the beginning or end. This allows for harmonic changes that complement the recorder line, a style continental musicians were already using but hadn't caught on in England yet.

I've also included selected pieces by Gottfried Finger from his Collection of Musick in Two Parts (1691).

As I've shown, the ground was the skeleton. The divisions were the flesh you put on it. And every performer would do it differently, showing off their particular technical facility, their melodic inventiveness, their grasp of the instrument's capabilities.

This edition aims to make the tradition accessible again, to show how recorder players, violinists, and viol players were all drawing from the same well, adapting the same material to their different needs. It's a window into a musical culture which was far more collaborative and fluid than we sometimes imagine. A culture where the line between composition and improvisation was genuinely blurred, where performance was always also a kind of creation.

Notes

Frank Kidson, 'John Playford, and 17th-Century Music Publishing', The Musical Quarterly 4, no. 4 (October 1918), 516.

Margaret Dean-Smith, 'English Tunes Common to Playford's "Dancing Master," the Keyboard Books and Traditional Songs and Dances', Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 79th Sess. (1952–1953), 6.

Kidson, 'John Playford', 516.

Kidson, 'John Playford', 527.

Frank Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher, John Walsh, His Successors, and Contemporaries', The Musical Quarterly 6, no. 3 (July 1920), 434.

Margaret C. Gilmore, 'A Note on Bass Viol Sources of The Division-Violin', Early Music 11, no. 2 (April 1983), 223.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223.

Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher', 431.

Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher', 434.

Kidson, 'John Playford', 522.

Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher', 434.

Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher', 438.

Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher', 439.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223.

Dean-Smith, 'English Tunes', 10.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223–224.

Gordon Dodd, 'Bass Viol Sources of The Division-Violin', Early Music 11, no. 4 (October 1983), 577.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 223–224.

Gilmore, 'Bass Viol Sources', 224.

Dean-Smith, 'English Tunes', 10.

Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher', 437.

Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher', 437–438.

Kidson, 'Handel's Publisher', 438.

Edward Huws Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice in the Early English Baroque,' The Galpin Society Journal 25 (1972): 67.

Thomas Mace, Musick's Monument (London, 1676), 207; quoted in Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice,' 67-68.

Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice,' 68.

Mace, Musick's Monument, quoted in Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice,' 70.

Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice,' 68-69.

Ibid., 68.

Vincent Duckles, 'The Gamble Manuscript as a Source of Continuo Song in England,' Journal of the American Musicological Society 1, no. 2 (1948): 25; Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice,' 69.

Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice,' 69.

Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice,' 71.

Duckles, 'The Gamble Manuscript,' 40; Jones, 'The Theorbo and Continuo Practice,' 71-72.

Viola d'Amore

Some insomniac Baroque courtier grafted sympathetic strings onto a viol, carved a leering Cupid on the scroll, and called it the viola of love .

What followed? This baby went rogue.

It spawned a whole dynasty of sound, a dozen offspring from Istanbul to Oslo. It survived its own extinction and utterly confounded (almost) every scholar who tried to pin down where it came from.